Collected memories

The most successful agents had histrionic skills adequate to this task but I didn’t, I realized about a month into the work. Nor was I willing resort to crass manipulations or outright lies, the bullshit part, that my bosses urged on me when my sales were slack, as they usually were. My strong point was listening.

Each week we had a meeting at the office. I got used to the catwalk three stories up; I focused my mind on the doughnuts at the back of the room. Eddie tried to pump us up by congratulating the most successful salespeople for the week. For the rest, he urged us on. “Never go home for the night on a ‘No’, always on a ‘Yes’,” he admonished one day. And then, “Go buy a new car or a new house. The debt will be a great motivator. It worked wonders for me.”

“But not for me,” I thought to myself. What about the six-month’s back rent that I owed and the collection agencies that kept calling?

After the meeting I went back to Ben’s office and picked up my new deck of yellow cards. The addresses were in Lincoln County around Troy and Elsbury, Missouri. Some of the people were farmers and some were workers laid-off from factory jobs in St. Louis—The country was in recession. One man, a machinist, was cutting firewood in the forest to support his family. Another had been a boxing champion in the Army years before but had suffered many concussions. We sat in his barn while I listened and he talked and cried.

Some people had problems with their Instant Issue accident policies. When it came to paying claims; confinement at home turned out to be hard to define. We were told just to listen and let the office handle these cases.

I kept a tally of the unemployed among my customers: ten percent just like the country then. Another man, in a trailer park, looked and walked like Toulouse-Lautrec, the artist. He had no legs below the knees from an auto accident in the Navy. Some invited me for dinner. Almost all were warm and welcoming.

As I drove home at night down US 61, I’d turn my dash lights way down and soak in the dark countryside as it sped past. I was at peace, for a while. I had sold a couple of policies but I didn’t feel right about it. I liked these people, and I felt sick when I took their money.

After two months in Lincoln County, the yellow cards led me back to St. Louis. My two small commission checks were nowhere near enough to cover my expenses. In desperation I plunged ahead in spite of the manipulative and dishonest work that I was supposed to be doing. My bosses said that my job was to create the need for our marvelous products, but these people didn’t need life insurance. They needed compassion which I tried to supply in my brief meetings with them.

The card named a single man, but a middle aged couple met me at the door of the house in a St. Louis County neighborhood. He was their son, now in his mid thirties. At age six, they told me, he and a friend had been playing with a gun. The bullet shattered his lower spine and they had cared for him ever since. He wasn’t home that afternoon, but at work. They saw the question in my eyes and explained: He has a wheel-chair equipped van that he drives to his business a few blocks away. He repairs sound equipment for musical groups. They gave me an address.

I found the building, a brick single-family home with bars on all the windows and the shades drawn. I knocked but no one answered. No answer again when I checked back later that day, and again the next. After a week there was a car parked in back and a young man answered the door. He was the business partner of my customer, he said, and offered to show me around. “We’ve had break-ins; that’s why the bars and shades. Druggies like to steal audio stuff.” There were some loudspeakers and amplifiers on the floor of one room, and a small electronics work-bench in another. All the walls in the house were painted black and the other rooms were empty. “He’s not here but you might try his parent’s house again.” I knew that he wouldn’t be an easy sale, but I was determined to track him down anyway. The mother told me to come back the next morning at eleven; her son should be out of the shower by then.

His special van was parked in the driveway when I got there. “He’s in his room dressing but he doesn’t want anyone to see him,” the mother said. “You might talk with him through the door.” I had burned almost two weeks trying to find this guy, so I knocked. “Yeah, who is it?” I introduced myself and gave him the canned sales pitch through the closed door. “No, I don’t need anything like that,” the voice came back. My job was done.

I made a couple of sales calls in Valley Park a few days before Christmas, 1981 and one or two afterwards. I went to Thomas, my boss, and said that I was quitting. “We were thinking that it might be a good idea, too,” he said. He wished me good luck.

A year later I was managing a movie theater in a St. Louis suburb, one of the Wehrenberg chain, with two screens. I didn’t get to choose the movies that we ran; booking was done by the central office. So when my boss told me that we would be showing “Bloodsucking Freaks,” I asked him to repeat the title. We both laughed, but I knew better than to question this choice. Maybe some other theater would get the next turkey that our chain had to take in its booking package. “Freaks” was a grade-D movie that belonged in a porn house or in a rural drive-in somewhere. Maybe eight people bought tickets to see this deplorable epic during the week that we had it. I watched about five minutes: several naked women were cannibalizing some guy in a prison cell. That was all I could take.

I came out of the storeroom one evening and thought I saw the back of a motorized wheel chair disappearing into the “Freaks” side of the house. I had a hunch and sat in my office until the show started. Then I took a tour of the parking lot and there it was: the wheel-chair van that I had spent two weeks pursuing when I was trying to sell life insurance.

I was busy counting receipts so I didn’t him leave the theater. A week or two later, I saw on the news that he and his partner had been arrested for selling drugs, big-time, out of his business and from the van. The news showed a shot of the house with the barred windows. No wonder he didn’t want to meet me. I could have been a cop.

About four years after I quit Penitential Life, I talked with a man I’d met a couple of times. He was a salesman who had sold everything from encyclopedias to Fuller brushes, all door-to-door cold calling.

“Yeah, I worked there too,” he said, when I mentioned my adventure in life insurance sales. We talked about Sam, the licensing teacher and how good he was. I asked about Eddie, the boss at the agency. “His wife got sick and you know he had their health insurance with Penitential Life.”

“Of course, who else?”

“Guess what? They reneged on his claim. Just about tore Eddie up. A few months later, he’s dead from a heart attack. Not even forty-five.”

It hadn’t occurred to me to smoke when I was in high school; both parents smoked unfiltered cigarettes, but among kids my age, only the thugs, greasers and delinquents did. None of the college bound kids smoked.

It all changed when I got there myself. I was 18 and devoid of social skills when I arrived at Middlebury College in the fall of 1957. Unable to make friends, I sought refuge in the college radio station, WRMC, where I hoped to sharpen my electronics skills and gain some degree of social acceptance. Maybe, I thought, the shared activity might generate some companionship. Besides, there were a couple of girls who worked at the station and maybe I could gather the courage to ask one of them out.

Most people on the radio station smoked. In fact, the American Tobacco Company paid for our United Press teletype service; all we had to do was play their Lucky Strike® commercials on the air. And it gave out little sample packs of five cigarettes each on campuses nationwide, including Middlebury.

In the dorm and at the radio station, the people who smoked seemed relaxed and at ease with each other. They didn’t have problems making friends or asking girls out. I picked up a sample pack of Lucky Strikes and smoked one. Of course, it tasted terrible, but I knew I had to stick with it if I wanted the social benefit that I saw in smoking. After I few days I got used to the taste and told my mother on the phone that I had started. “I’m sorry to hear that,” she said, “but of course Joe and I have smoked for years. I guess everyone does.”

Later that fall Middlebury’s fraternities held their annual “rush,” in which they looked over the male members of the freshmen class for potential members. Each of the ten fraternities hosted events called smokers on Friday and Saturday evenings which we attended in groups over a period of several weeks. I felt no less awkward and embarrassed at these gatherings than I had before, even with a cigarette in my hand or sticking out of my mouth. And none of the fraternities selected me; instead I wound up in an independent mens club.

I kept smoking unfiltered Luckies throughout college and succeeded in making a few friends; some smoked and some didn’t. Two of them had pipes which required constant reaming and scraping with a special tool they carried. When I tried one it tasted terrible in spite of the pleasant aroma.

In my first year of graduate school at the University of Vermont in 1961, I met a young woman, a non-smoker, who became my fiancé. Her name was Helene and after our engagement two years later she produced a very funny hand-drawn cartoon showing what I looked like as a smoker. There were spikes of fur coming out of my eyeballs and mouth, ugly spots on my face and hair sticking out in all directions. The inspiration for her sketch had come from the Surgeon General’s first report on the health hazards of smoking issued in January, 1964.

By that time, I had transferred to Princeton to complete my doctorate and very few of the people in the lab where I worked smoked. After six years of what I called real cigarettes—those without filters, I quit cold turkey. I had no trouble, but I joked that if I ever had another cigarette, I would inhale so deeply and with such satisfaction that the smoke would pour out the eyelets where I laced up my shoes.

Helene and I married in 1965 and moved back to Middlebury where I had a teaching job. Our daughter Hanna was born three years later. A year after that, in 1969, we moved to St. Louis, where I took a research appointment, but Helene was not happy. We separated in August 1970 and divorced in May 1971.

The stress was too much; I powered myself through the initial months with Librium and attempted to cover my anxiety and grief with a return to cigarettes. This time I chose filters as less risky than what I had consumed before. I smoked Kent Golden Lights® for 16 years.

In 1985 I took two smoking cessation classes, and in the second one acquired some samples of Nicorette®, the nicotine chewing gum. I worked then for McDonnell Douglas and carried the Nicorette in my brief case every day until February 28, 1986 when the boss decreed that smokers would have to move to a separate part of the office. I dropped my cigarettes into the wastebasket and took out the nicotine gum. I haven’t smoked since. It wasn’t until 1996, 38 years after I started smoking and 10 years after I quit, that second hand smoke began to irritate my eyes.

When I began my job in the Department of Otolaryngology at Washington University Medical School in St. Louis, in 1969, I kept my ears open and picked up all sorts of medical information. Sometimes it came from the grand rounds I attended every week, where cases and scientific papers were discussed or simply from chatting with the residents that I taught in class or who worked in my lab. After I had been there a few years, I had a question for one these physicians, a guy who had some expertise in respiratory dynamics.

“Irv,” I began, “I think I have a deviated septum and I have trouble breathing though my right nostril. Should I do anything about it?” “Well, you might think about it,” he said. “It can lead to trouble later in sleeping or even in your bronchial tubes, sinuses or lungs.” We both knew that surgery was the only option – something called a “submucosal resection” done under local anesthesia. What Irv didn’t have to say was that smoking cigarettes, which I did at two packs a day, was a far greater risk to my respiration than any deviation of my septum could be. But Irv wasn’t my physician, and the residents knew not to give unsolicited medical advice to their colleagues and friends.

It took another year of stuffiness and obstruction to convince me to get it done. I wasn’t getting any air at all on the right side when I asked Irv to suggest a surgeon. “Don Sessions is pretty good with noses,” he replied. “You’ll be in and out in less than a half hour.” A couple of days later in his office, Don took a look and said, “Yup. It sure is. Let’s get you scheduled.”

I checked into Barnes about a week later in the early fall of 1977, a couple of months short of my fortieth birthday. My girlfriend Nancy had driven me and stayed with me in the room for an hour or so. When I said that I was frightened she reminded me how minor the surgery really was. I calmed down, and after she left, a resident came in to give me a pre-op physical. “Hey, chief, aren’t you the guy who taught us about cochlear microphonics and all that auditory stuff? “Yeah, that was me,” I replied as he checked me over. When I woke up the next morning I wanted to reassure myself with my usual morning routine of shaving and showering—and smoking a couple of cigarettes which was allowed then in hospital rooms.

After I rode a gurney to the OR, a nurse pinned me to the table with a sheet and started an IV. I was still scared, and it must have shown. “Would you like a little Valium to settle you down?” she asked. I nodded. “Yeah,” she said, “here it comes.”

Then Don Sessions came in along with a couple of residents whose voices I recognized from behind their surgical masks. The nurse scrubbed my face with Betadyne and placed a drape over my eyes and a second one over my lower jaw.

“OK, here goes,” Don said as he jabbed me with a long needle, right above my upper lip, directing it from left to right. It hurt like hell. “Scream, curse, do whatever you need to,” he said as he emptied half the syringe into me. Then another shot in the same place, this time from right to left, followed by two more directed upward along the outside of my nose. My face was starting to feel numb. After two more shots inside my nose, Don said, “Here’s a little nose candy,” and placed some powdered cocaine up inside each nostril.

After that there was a lot of scraping, crunching and chiseling. Maybe it was the Valium and cocaine but I didn’t mind. I’d had a lot of dental work done under local anesthesia, and this didn’t seem much worse. But then from under the drape I saw a long chisel headed toward me. “Now just give it a hard tap,” Don told the resident who was holding small mallet. My head shook with the impact. “No, you’ve got to belt it lot harder,” Don said. Now I was scared. Was this the resident’s first try? Would the chisel go too far this time and plunge into my eye or my brain?” There was another sharp jolt and my head shook again. “OK, there it is.” And he held up a triangular piece of bone for me to see.

“We’ll stitch you up now. We’re due at Stan Musial and Biggie’s for lunch, and we have to get moving.” I felt a twinge of disappointment; had I not been pinned down to the operating table, I could have been joining them at the restaurant. He installed a plastic splint inside my nose on both sides and pinned it in place with a heavy suture that he drove through from one side to another with a straight needle. Then he stuffed what seemed like several yards of gauze packing into my nose. Of course I will still very numb.

Back in my room, the nurse put an oxygen mask on my face since now I could breathe only through my mouth. I reached for the phone to call my parents in Marblehead and spoke with my father assuring him that I come through the operation OK. Then I dozed off until the resident came in to check up on me. After he left, I wondered if I could smoke with only my mouth to breathe through. I went in to the little bathroom and lit a cigarette. I took a puff inhaling the smoke. Then I blew it out—no problem.

I went home the next morning and stayed there for a week. I was sore and there was a little bruising around the bridge of my nose, but I could sleep OK. I got used to breathing though my mouth. Of course the packing was uncomfortable; it looked terrible and it dripped. At the end of the week I went back for my check up. Don was out of town, so another staff physician took out the splint and all packing and cleaned me up. I could breathe again.

Back at work I joined my usual lunch companion in the cafeteria: Roy Peterson, a professor of anatomy who supervised the laboratory where the medical students dissected their cadavers. I told him about the little piece of bone they had taken out. “Yeah, that’s the vomer,” Roy said. “If you like we can go upstairs and I show you on one of our cadaver skulls.” I was curious and wanted to see what the bone looked like in its normal position.

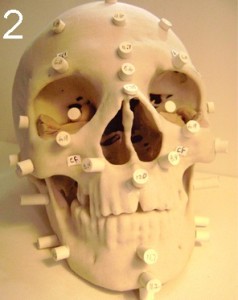

A cast from an Egyptian mummy showing a right-deviated nasal septum. The numbered pegs aid in reconstruction of the face.

We had to go through the dissection lab to get to the display cases with the skulls, and I was relieved that all the bodies were covered with sheets. I may not seem squeamish, but partially dissected people are too much. At the display case, he pointed out the bony parts of the nasal septum that remained in the skull. “There’s the vomer right at the base of the nasal opening—see, that little triangular piece. You know that septal deviations are very common; you can even see it this skull. It’s usually not bad enough to obstruct breathing, though. They even found deviations in Egyptian mummies.”

I wondered if the ancient Egyptians had the same trouble breathing that I had before the surgery. Probably not I had to admit. They didn’t smoke.

The large punchbowl looked so inviting on the table in the woman’s apartment at the Town and Country Apartments in St. Louis where I had recently moved in 1970 when I was 31. I had separated from my wife at the end of August and had chosen the Town and Country for its proximity to my work at Washington University Medical School just around the corner. I had met a few of the other inhabitants, mostly med school employees and physicians around my age. One of them, a librarian who worked on the main campus, had invited me to a small Christmas party in her apartment.

I was planning to stop by on my way a larger gathering that Saturday, to be held on the top floor of the Olin Residence, a dorm for medical students not far from my apartment. The party in Olin was put on every year by the residents in the Department of Otolaryngology (Ear, Nose and Throat) in which I held a teaching appointment. Everyone from the department was there: faculty, staff and, of course, the residents, who produced a video skit each year.

The punch at the little party in my apartment building had maraschino cherries, pineapple chucks, tangerine wedges and orange slices floating on the top, along with ice cubes. There were other refreshments, too: Christmas cookies and fudge. I hadn’t eaten supper because I knew there’d be lots to eat.

I’m very nervous in social settings where I don’t know most of the people, and in those years I smoked to cover my unease. Besides, I’m no good at small talk, and at parties I head to the food table when my conversational gambits fall flat.

I didn’t really know what was in the Christmas drink. If I had to guess, I’d say canned Hawaiian Punch with ginger ale, pineapple juice and a little sugar mixed in—nothing more. After failing to start up sustainable conversations with the only two people I knew, I went back for a few more cups. I saw no harm; it just tasted sweet. A little while later, I thanked the hostess and headed to the big party at Olin.

When I got off the elevator on the top floor, I needed the restroom—no surprise with all that fluid on board. Inside I heard retching sounds from one of the stalls, and one of the residents I had taught staggered out, shaking his head. “Wow, that’s strong stuff in there,” he said, and bent over the sink to rinse his mouth.

I found the bar, and after what I had witnessed in the mens room, decided on a gin and tonic. “Just a little gin,” I said. I took a sip and turned around. On my left was a row of chairs aligned against the windows, and sitting in them were a few resident’s wives, and several faculty couples. Most of my colleagues were a decade or so older than I was, but one, Don Sessions, was about my age. He and his wife Jan had recently moved to St. Louis from Alaska, where he had fulfilled his military obligation at an Air Force Hospital. They were a relaxed young couple, and before separating, my wife and I had enjoyed chatting with them.

To my right, opposite the chairs was the food table with a large punch bowl, but unlike the one at the party in my apartment building, this bowl didn’t contain punch. Instead it was filled with a special dipping sauce prepared by one of our residents, Dr. Frank Lucente, who had boasted of his culinary skills and had promised a special treat for the annual party. Containing unique ingredients, the sauce was intended to complement various crackers, breads, celery sticks and other crudités that he supplied. It was his pièce de résistance and with artful garnishing around the rim, it seemed so attractive that no one dared take the first scoop, lest an ugly divot mar the glistening surface.

I was debating whether to be first to sample Frank’s work of art when the room began to spin around me. I lurched back and forth a couple times and forced my feet with deliberate effort to convey me back to the mens room where I dove into a stall. Like the resident before me, I staggered to the sink afterward to rinse my mouth and wash my face. Then I felt OK.

Back at the bar, I asked for a ginger ale and took a couple of wary sips. No one had yet sullied the surface of Lucente’s dipping sauce. As I walked past it, the room spun again, this time with greater violence than before. My feet gave way and I stuck out my hand to steady myself, plunging it nearly to the elbow in the bowl of Frank’s culinary creation. I looked with horror and lurched in the opposite direction, landing in Don Session’s lap. Thank God it was Don and not one of the senior guys.

How I made it back to the mens room I don’t remember, but when I got there, there was another resident passed out on the floor. I jumped back into the stall and rinsed my mouth afterwards. The guy on the floor was groaning. Beside me at the next sink was a young Brazilian physician who worked in my lab. He grinned at me and laughed. I looked at him and said, “Erol, I think I’ve had enough. I’ll see you Monday.”

I stumbled back to my apartment, grateful that I didn’t needed to drive. When I saw my hostess from the small party, I didn’t have to ask her what else had been in her wonderful Christmas punch. I already knew.