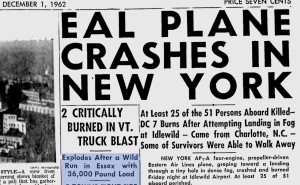

Headline in the Lewiston, Maine, Sun, announcing two crashes that affected me and my family on Friday, November 30, 1962.

One morning in late November 1962, when I was a graduate student at the University of Vermont in Burlington, we awoke to a power failure. On my battery radio I heard that a chemical tank truck had overturned and caught fire, taking out a Vermont Electric substation on Route 15 in Essex Junction. With no electricity there would be no classes for me to take or teach. As a lifelong fire chaser I had no choice but to head north to check out the accident scene. I parked some distance from the wreck and approached cautiously. The tractor and trailer had separated in the crash, with the tractor across the road halfway up a grassy hill. The tanker was resting on its side against the chain link fence surrounding the substation and Essex Junction volunteer firemen were cooling it with water on the outside and pumping a small amount of foam through its open hatch.

A crash truck from the Burlington Municipal Airport stood by. I joined a small group of spectators who were surveying the scene from the hill where the tractor had stopped. Standing with us were some Vermont Electric linemen whose access to the substation was blocked. Suddenly and without warning, the tanker ignited with a loud “whomp” and sent a large blast of flame directly at us. I threw myself to the ground just as it passed over me, but one of the linemen was less fortunate and received flash burns to his face and arms.

We stood. The lineman was in shock walking around and calling for an ambulance. We got him to sit down and I checked my back. I was lucky that only my neck hairs were singed, but the fur lining in the hood of my parka was burned right off. I looked at the tanker and saw the firemen attending to a fallen comrade right by the hatch. I heard the airport crash truck revving it’s engine to propel foam onto the wreck from the nozzle on its roof.

This incident played out in the pages of the Burlington Free Press for a couple of weeks. The tanker had contained a volatile and toxic industrial chemical known as vinyl acetate. The truck driver, Marcel Duteau, was heading north to Montreal from Leominster, Mass. when his brakes failed on a sharp downhill curve in the road, as he told police at the scene. He then walked into Essex Junction and boarded a bus for Montreal without telling anyone what was in the tank or what it could do.

The burned Essex Junction fireman spent several months in the hospital, but did recover. I didn’t know until I discovered an AP report on the internet that a second person, a Burlington Free Press photographer, had been burned just as badly as the firefighter and that his camera had melted. My small group of spectators who were tending to the burned lineman had our backs to the tanker, and didn’t notice the more serious burn victims.

My mother had given me the burned parka during my undergraduate days, and I didn’t dare wear it again in her presence. She would have given me hell for placing myself in such danger.

The tanker explosion happened on Friday, November 30, 1962. Only two days later, on Sunday, December 2, my mother called from Marblehead to tell me that my cousin Joan’s husband had been killed that same Friday evening in plane crash at Idlewild (now Kennedy) Airport in New York. Joan was my father’s neice, who had grown up in Danvers, Mass. and had married her high school sweetheart, “Butch” Voorhees. After serving in the Air Force, Butch had joined Eastern Airlines, and was working as flight engineer on a propeller-driven Douglas DC-7B which crashed in fog while attempting a go-around after a flight from Charlotte, North Carolina.

There had been some confusion in the schedule and Butch did not appear on the crew manifest until Eastern Airlines rechecked and found that he had substituted at the last minute for the other engineer. The news came through to my cousin Joan late Saturday afternoon at her home in Long Island. Joan’s father (my uncle Paul) who by then had separated from my aunt Millie, jumped into his car and made the trip from Marblehead to Long Island in three and a half hours, at least an hour and a half short of the usual time. Everyone in the cockpit had been killed, but twenty-five of forty-six passengers survived.

Joan had three small children playing inside the house, but she was outside raking leaves in her bluejeans when the two senior Eastern Airlines captains drove up to deliver the news. Joan is short and very thin, and the two officials mistook her for a child and asked if her mother was home, as she told me years later.

During the last week of November 1962, there were five other fatal airline crashes worldwide. Today, thanks to much improved safety provisions airline crashes like the one that killed Butch are rare. In 1962, the Essex Junction firefighters had no idea of what they were dealing with in the crashed tanker, but now trucks and trains carrying hazardous material carry numbered warning placards that are keyed to specific instructions for emergency responders.

Next week: Some comments.