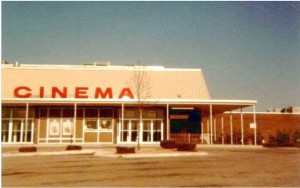

The new theater had just two screens with a small concession stand and was located in a shopping mall at the intersection of New Halls Ferry Road and Lindbergh Boulevard in Florissant, Mo. Cross Keys, built in 1969, contained a number of small businesses, a popular restaurant, and a section of office space used by the McDonnell-Douglas Aircraft Company. The entrance to the theater, which Wehrenberg had acquired from the old Arthur chain, was not visible from the road but only from the rear parking lot. There was no marquee above the entrance, only two signs in the parking lot that announced the movies playing each week.

My district manager Paul, who was slender with brown hair, and about my age and height, explained some of the reasons for the daily inventories of the concession stand candy bars. He was friendly and gave me lots of tips about running a theater. “We had a manager,” he said, “who stole from the storeroom and sold the candy bars out of the trunk of his car. The daily inventories took care of him right away.” I understood that he might have been warning me against similar temptations.

I had two regular assistant managers: Joseph, a young African-American man with a recent business college degree and a young woman Sharon—short, dark-haired, and in her thirties, who had worked part-time for the theater chain for many years. Joseph was slender, maybe an inch shorter than I was, and was always in neat gray or brown suit. He seemed aloof, but was always dignified and courteous. Sharon, the other assistant, was efficient and very competent at all the theater tasks, but she wasn’t very friendly either.

Julie, in contrast, was a gracious and warm young woman who filled in at various theaters. David, the blond man who had interviewed me originally for the job, also helped out at indoor theaters during the off-season at his drive-in. He wanted to become a radio announcer. To that end he attended daytime classes at a proprietary broadcast school in Clayton, the St. Louis County seat. The school, which I walked by often had one of its studios set up behind the front window, both as an attraction for prospective students and to give the public a look inside radio broadcasting.

New movies started on Friday to capitalize on the weekend. Each Thursday before closing, we were supposed to make a recorded telephone message for the theater, listing the movies and show times for the following week. Even after rehearsing the lengthy announcement, it could be difficult to record it correctly, especially if other employees were around the office when you were trying to do it, as David explained,

Once, I was making the recording, and right near the end, I realized that I had made a mistake, but I continued speaking, filling the tape with progressively worse profanity and made-up salacious movie titles. Then I called Julie into the office to check the recording. You should have seen her face.

I quickly mastered the technicalities of running Cross Keys. I balanced the daily and weekly cash and inventories and many weeks received a twenty-five dollar bonus with my paycheck for the accuracy of my accounting. The figures were recorded by hand on a large paper form with two carbon copies required. If you made a mistake, you could erase the top copy but had to use Wite’Out® on the carbons, sometimes creating a mess. Errors crept in on busy weekends from cash register mistakes made by the girls dealing with large crowds at the concessions stand, or from miscounts in the inventories or ticket sales.

The whole system had been perfected before computers by a man named Smith in the central office who was in charge of all Wehrenberg concession stands. He was not popular with the managers because of his obsessive insistence on accuracy, but I could tell that he was very smart. He was the only person who knew how to program every type of cash register in the entire chain, entering the correct codes for the sales taxes which differed from one municipality to another. Besides, his system eliminated pilferage and till-tapping by dishonest employees.

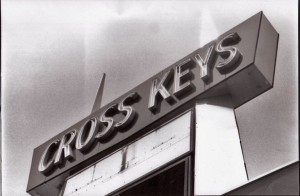

At Cross Keys, I had several teen-age employees, most of whom were reliable and fun to work with. An exception was a young African-American usher named Karl. (His name like others in this story has been changed.) He was short and slender. One Thursday, when my chief usher Mark was off duty, I sent Karl out to the parking lot with the red plastic letters needed to change the marquee signs for the theater. The signs had back-lighted panels with narrow horizontal rods from which the letters announcing the movies were suspended. To change the letters the ushers used a long aluminum pole with a suction cup on the end to take down the departing movie titles and put up the new ones.

The old Cross Keys sign announcing the 2003 renovation. Here’s where the movie titles were displayed for the cinema in back. Horizontal rods for hanging the plastic letters were in the white section near the top. Photo taken after the theater closed.

I drove home that night without checking the signs. When came back Friday afternoon, I saw that the letters on the sign were in the wrong positions and the movie titles were misspelled. After Mark fixed the signs, I felt relieved that Karl, the errant usher, didn’t have the imagination or wit to put something malicious or obscene on our marquees.

During Karl’s shifts, his friends occasionally attended the theater. Sometimes they paid, but other times, I suspected, he let them in through the exit doors. He and his friends once sat in the back of the theater talking and disturbing paying patrons, who complained to me.

After a few of these incidents, I put him on suspension, but he said he would appeal to my district manager Paul. Karl had the backing of my assistant managers, Joseph and Sharon, who told me not to let the situation escalate to the manager’s level. Sharon, the dark-haired woman in her thirties, said, “I’ve known Paul a lot longer than you have and I know that he doesn’t want to be bothered with details like this.” I agreed, with reluctance, to drop Karl’s suspension. I learned later that Sharon was lying about Paul and, with Joseph, was trying to make trouble for me.

Why would Paul and Sharon try to undermine my authority in running the theater? There were two things, I think: Karl the usher and Joseph the assistant manager were African-Americans with whom I felt uncomfortable because they didn’t seem friendly. I never made the attempt to know them well. After all, I was their supervisor, and it didn’t seem appropriate. As an employee, Karl the usher got off on the wrong foot with me when he garbled the marquee signs in the parking lot. And, of course, there was racial unease on both sides that I didn’t feel with the friendly African-American employees and coworkers

With Joseph, the assistant manager, I overreacted in a situation and said something I shouldn’t have. My boss Paul had asked me to have a small part of the concession stand repainted. I asked to Joseph to do it. Several days passed and nothing happened. Paul could appear any day and see that it hadn’t been done and I’d be in trouble, I thought.

I grew impatient and told Joseph that if he wanted to continue working at the theater, he should get the little job done. He got angry and said that I had no right to speak to him that way. The next day he did the painting. We were both caught in a supervisory misunderstanding with racial overtones that I didn’t know how to handle.

One of the Cross Keys road signs with mounting rods for movie titles. Photo taken after the theater closed in 1999.

With Sharon, I needed to contact her one evening from home where I didn’t have the telephone list. With no cell-phones or emails, I resorted to the phone book and found a number listed for a person with her unusual last name. I called and reached a woman who agreed to relay a message to her. The next day, she came in very angry at me and insisted that I never try to contact her through a relative. I didn’t understand that either.

I should have consulted my district manager Paul as soon as these employee problems arose, but I was afraid he’d let me go. My fear was overblown. Paul was a decent man who would have the supplied the guidance I needed.

Our theater was cleaned each morning by an elderly couple who I met only once because our shifts never overlapped, but when I arrived each afternoon the place was sparkly clean. One night driving home after a busy evening I noticed that one lens was missing from my eyeglasses. It had popped out before a few times and I had picked it up and set it back in the frame. This time I was out of luck. It was too far to drive back to the theater, turn on all the lights and do an exhaustive search while I was tired and needed sleep more than anything else. I couldn’t afford new glasses, but I could get along OK with just one lens, at least for a while. Thank God they weren’t bifocals.

In the morning I called the theater hoping to catch the cleaning couple close enough to the lobby to hear the phone ring in the office. One of them answered and said they’d be on the lookout for the lens. Less than a half hour later they called back; the missing lens was on the floor at the back of one the auditoriums.

It was time to meet them in person. I jumped into my car and drove the 13 miles up the theater to thank them and to collect my lens. I popped the lens back in and, at home, added a drop of super-glue to hold it in for good.

Most of the time, the Cross Keys Theater was very quiet, even on weekends. Wehrenberg didn’t put high-grossing first-run films in an obscure, difficult-to-find backwater cinema like ours. We usually got grade-B and below pictures or popular shows nearing the ends of their runs. But there were a couple of exceptions.

Nest time – Inchon