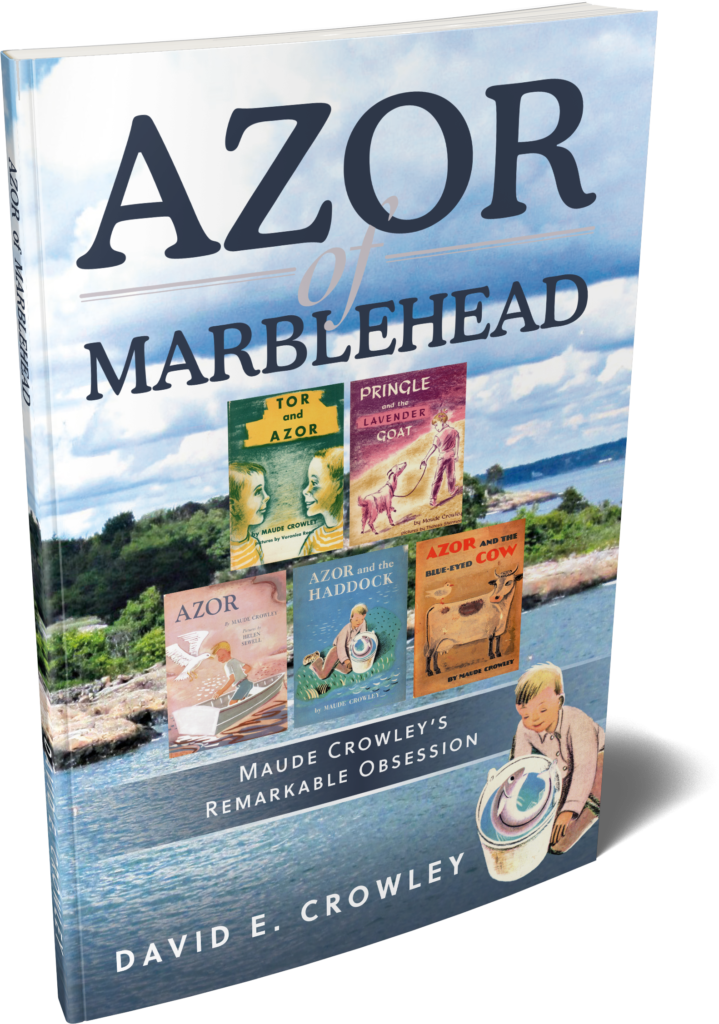

Contact dave@davidecrowley.com to order at a hefty discount from the original price of $21.95! Now $14.95 including priority shipping

Check out the synopsis to learn more:

Contact dave@davidecrowley.com to order at a hefty discount from the original price of $21.95! Now $14.95 including priority shipping

Check out the synopsis to learn more:

A tasteful Vermont road sign as illustrated by Ryan Fowler of Native Vermont Studio

It was bound to happen sometime—I would use an image in one of my blog posts (Inside Seashell City ) that was copyrighted artwork created by someone else. In this case what I mistook for a simple photo of an old road sign in Vermont that I found on the internet was really an illustration produced by Ryan Fowler of Native Vermont Studio, as he graciously reminded me in an email last night. I should, of course, have sought his first permission first. Please visit his website to check out his delightful creations.

I’ve got to credit my mother, Maude Crowley, for setting me on the path to becoming a writer. Not only did she insist that my childhood speech be perfect in grammar and syntax, but she wrote five children’s books. The Azor series, published between 1948 and 1955, featured the exploits of a Marblehead boy much like me and his friends who were based on my pals Chris and Erik Brown. My father, Joe Crowley, a Boston newspaper editor, was also an expert in spelling and grammar. He reinforced my mother’s teaching and corrected me on anything she missed, which wasn’t much.

My mother and her sister Therese had graduate degrees in journalism from Columbia University in New York. Both worked as reporters in New York, and Therese co-wrote a study of laundry workers there. In 1931 she married a young reporter for the New York World, Joe Mitchell, who became a celebrated writer for the New Yorker. Disdaining celebrities, he wrote with compassion about obscure and eccentric New Yorkers, turning them into memorable characters. “Joseph Mitchell transformed journalism into art,” wrote Newsweek in its 1992 review of Up in the Old Hotel, a long-awaited collection of his work.

I saw my uncle at least twice a year during our family visits to New York and when he came to Marblehead with Therese and my cousins Nora and Elizabeth. We last met in New York in 1993, just after the publication of Up in the Old Hotel. Joe was gloomy as he often was, and as we walked the back streets around the Fulton Fish Market he said, “You know, David, there just aren’t any people left in New York like the ones I wrote about.”

Before he died in 1996 he had agreed to a film based on his work. Joe Gould’s Secret appeared in 2000 and featured Stanley Tucci as Mitchell and Ian Holm as Gould, a literate and cultured inhabitant of Greenwich Village who lived like a derelict. On February 11, 2013, The New Yorker published “Street Life” a fragment of Joe’s unfinished memoir, discovered by Thomas Kunkel who is writing his biography.

Therese who died in 1980 was a professional photographer, and in 2002 my cousin Nora published a collection of her mother’s photos from New York in the 1930s along with quotes her father’s books. In her introduction, Nora wrote,

…I read them [reissues of Joe’s books] closely for the first time in years, with my mother’s pictures freshly in my mind, I was overcome by the traces of each in the other. The words and music were such perfect companions that putting them together became an almost obsessive exercise. As I watched them watching the men on lunch break and the shoeshine boys and the unemployed men at Union Square and the waiter writing the day’s menu on the restaurant window, they were resurrected. (©The Recorder, The Journal of the American Irish Historical Society, Spring 2002)

Some people, like Nora, who don’t write often for publication, have no trouble expressing themselves when they speak of people they love. I can say the same about my daughter Hanna who reached the difficult decision in 2001 to send my special-needs granddaughter to a boarding school:

It was as if somebody pumped oxygen into her finally and all of the other children as well and she felt comfortable to be what she is…When it came time for my husband and I to leave, we looked around for her to say, “good-bye.” We finally found her surrounded by a group of boys and girls, who were all talking, laughing and having fun. We did not want to break up the party, so we stood back, watched, and cried in happiness over this vision of her contentment. Finally, one kid noticed us and poked her to let her know that her parents were standing by. She extracted herself and ran over and we let her know we were leaving and she gave us both big hugs. My husband and I cried, but she did not. She said, “Mom, don’t worry about me, I’ll do great!” And, she is. (© Woodbury Reports, Inc “Was It The Right Decision?” Hanna Ryan, April 2001)

Next week: Dave’s grandfather and Theodore Roosevelt