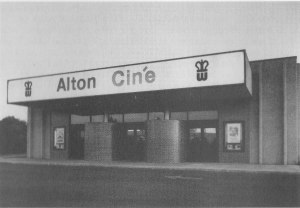

Wehrenberg’s Alton Twin Cinema opened in 1976 and closed in 1998.

Sometime in the fall of 1982 the Wehrenberg management began to prepare its managers and assistants for the possibility of a projectionists’ strike. The old contract had expired on August 31, 1982 and Wehrenberg wanted to reduce the projectionists’ minimum shift from 5 to 4 hours and allow its managers to run the projectors after end of the union worker’s shifts, according to a story in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.The hard line taken by the chain in its negotiations with the union was solidified by problems like the disaster on September 17, 1982 when the hiring hall sent an untrained substitute to my theater for the showing of Inchon and E.T. resulting in the refund to almost 800 tickets to angry customers, in cash.

We managers and assistants would have to learn to run the projectors ourselves if the projectionists struck. We couldn’t practice in union theaters on the Missouri side of the Mississippi River, but we could learn in Alton, Illinois, where Wehrenberg had a dual-screen non-union theater.

Since the Alton Cinema was open to the public only in the evening, we trained in the afternoon. We rotated through the projection booth, learning first how to deal with the traditional film reels and dual projectors, and later with the platter projection systems that were used in most of Wehrenberg’s Missouri cinemas, but were not installed in Alton until the winter of 1983.

These platters were identical to those in Cross Keys, the theater I managed in Florissant and if we were weren’t careful we’d wind up with hundreds of feet of film on the floor, and refunds too.

My two regular projectionists at Cross Keys, Jerry and Eric, seemed friendly enough and hoped that a strike wouldn’t happen. Like most movie projectionists in St. Louis, Jerry and Eric were part-timers with other jobs. Eric, for instance, worked in a large postal sorting facility during the day.

I learned from another manager that negotiations were breaking down, and that there would be a strike vote after the theaters closed on March 8, 1983. The projectionists voted 66 to 4 to authorize the strike, according to the Post-Dispatch. Mediation failed and the union called for the walkout to begin on Saturday April 2.

Friday evening my district manager Paul waited with me at the theater. Eric, the projectionist on duty, closed the booth and headed for the door, I thanked him for his work, as I did all employees when they left—a practice I learned from Randy, my first manager at the Halls Ferry Eight. Worried that the strike might bring violence, Paul brought along his son’s baseball bat as possible protection. At around one in the morning, he and I closed the theater and headed for home.

At the ten the next morning my phone rang. It was David, the drive-in manager: “You’d better get up here to Cross Keys. There’s a picket line, but we’re going to open tonight and show the films ourselves. We need to practice in this booth.” I got to the theater and David and I, with help from Paul, began to load and unload the platters, making sure that we could project the movies and that the film would feed smoothly from one platter to the next as intended.

Crossing the picket line was uncomfortable for me because I believed in the union movement. As a manager I made less money per hour than they did, and I knew about the striker’s day jobs. But it was my job to be in the theater. A couple of strikers waved at me and laughed.

The strike vote, we learned, had passed only on the condition that the other chain in St. Louis, AMC, and few independent theaters, not be struck—only Wehrenberg. The majority authorizing the strike included many projectionists who wouldn’t be forfeiting their own paychecks.

The theaters ran reasonably well for a few days with managers and assistants in the projection booths. The picket lines had the beneficial effect for us of keeping the audiences small as we were getting used to the equipment. But, late Sunday night, a projector lamp burned out in one my two auditoriums. Fortunately, no one was in the theater. It seemed that Eric, before he left to go on strike, had cranked up the lamp voltage to maximum, to ensure that it would burn out quickly. He was on the picket line laughing when I entered the theater the next day with the two new lamps that I picked up at Wehrenberg headquarters.

The chain’s management knew that we couldn’t operate for very long with managers in the booths, and towards the end of the first week of the strike they placed ads for substitutes, or scabs. With unemployment around 10 percent in the St. Louis region, many qualified men with good mechanical abilities came forward.

The March 8, 1983 vote to authorize a strike of Wehrenberg Theaters by union projectionists, as reported in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch

One was a retired Navy Chief Petty Officer and skilled hydraulic technician, a pleasant man in his early forties who had been laid off from his union job in an industrial control factory. He didn’t like crossing the picket line any more than I did, but he had an answer for the striking projectionists who harassed him for disloyalty. “I told them,” he said, “that my old union wasn’t putting any food on my family’s table and that Wehrenberg was.”

Next time – Antics