A Vermont road in the fall

I was drawn to Vermont in my teens by Kenneth Robert’s novels about the French and Indian and Revolutionary Wars. The heroic people and evocative names in his stories kindled my love of history and my romantic dream of living close to the sites where these historic events took place. When the acceptance letter from Middlebury College arrived in the spring of 1957 I was overjoyed. Visions of adventure and love among the mountains and along the lake described with such appeal in Robert’s books consumed my imagination as I set out for college.

The reality of Vermont’s beauty exceeded anything Roberts had described. The late afternoon light against the lush green hills was luminous, sparkling and dense, like a golden sea of air. College life was tough—devoid of adventure or love, in my case — but the appeal of the wonderful mountains, hills, lakes, villages and farms more than made up for my troubles.

During my years at Middlebury and at UVM in Burlington I took little notice of the tourist attractions that lined US Route 7, the main highway that linked Connecticut to the Canadian border. Some were tacky but most fit in gracefully with the surrounding scenery. There were reasonably-priced antiques, maple syrup cookeries, rustic cabins, and restaurants offering home cooked meals. Every item and ingredient was guaranteed to be absolutely fresh, entirely local, and manufactured reverentially by hand. Their billboards didn’t seem any worse than those of other tourist states. Like the Burma Shave signs they conformed to their commercial purpose and to the surrounding landscape which they refrained, for the most part, from obscuring. That’s how it seemed in 1963, when I left the state for graduate study at Princeton.

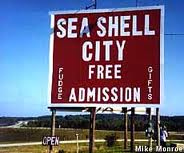

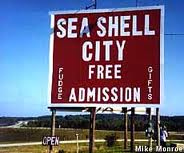

When I returned to Middlebury with my wife to teach in 1966, one business, just south of the town on the east side US Route 7, had altered this peaceful landscape. Its proprietors must have studied the relative uniformity and approximations to acceptable taste displayed by existing billboards and concluded that ordinary signs couldn’t do justice to their extraordinary attraction. They plastered every US highway leading into and through Vermont with what must have been at over a hundred signs. A modest billboard in Connecticut, white with red letters, along US Route 7 proclaimed that rare and exotic treasures from the seven seas, shells not found in any zoological collection because of extreme dangers involved in collecting them, were to be seen a mere two-hundred miles to the north on Route 7 at the amazing and electrifying “Sea Shell City.”

A similar attraction in Michigan. Photo by Mike Monroe.

Once you crossed into Vermont, any sign of restraint in the size and placement of the notices vanished. And, as you got closer to Middlebury, they got bigger, and more frequent. A billboard south of Rutland clarified what the sign in Connecticut meant by danger: “See the Giant Man-Eating Clam” “Only one mile ahead, on the right,” announced the penultimate billboard several miles north of Brandon, Middlebury’s neighbor to the south. This sign was so large that it obscured the Green Mountain range for a moment as you drove by. And finally it appeared: your ultimate reward for having endured two-hundred miles of two-lane road, often stuck behind trucks, travel trailers, and farm implements. White with huge red letters, the sign was so tall that you had to crane your neck back in your car seat to comprehend its upper reaches and it bore the unmistakable simple declarative sentence: “THIS IS IT!”

Your eyes were drawn involuntary to the right to behold the establishment itself: a modest dirt parking lot with at most three cars parked in front and a Quonset hut maybe sixty feet long and twenty feet wide. We drove by it dozens of times during our three years in Middlebury, always in too much of a rush to stop in and check it out. Friends told us that it was a retired couple who spent the winter in Florida collecting the shells, and then came up for the tourist season to sell them.

I had to have a look. There were no cars in the lot the day we interrupted our errands to pull in and to sample the wonders of Seashell City ourselves. We got out and approached the front door. The top half of the front door was a dirty window, and someone had Scotch-taped a paper plate to the glass from the inside. In pencil was one word: “Closed.” I guess they’d blown their sign budget on the billboards.

Next week: Inside Seashell City