Woody Allen’s imagination at work in Hanna and Her Sisters (1986)

In 2006 I went to an ear specialist to check out the mild deafness and stuffiness in my right ear that had persisted for two months. She looked in my ear and at my hearing test. “Let’s get an MRI,” she said. “With the MRI, we can check out muscles of the Eustachian tube and also see if there might be a small benign tumor on the hearing nerve. Why don’t you come back in two weeks.”

I was scared. I knew about acoustic tumors, to which she was referring. Hadn’t I spent five year researching diagnostics tools for them in the 1970s at Washington University Medical School? These rare tumors are benign, but they grow close to your brain and threaten vital functions like breathing. Surgery to remove them involves a long recovery and can destroy your hearing and balance. Few surgeons, I feared, had enough experience with this delicate surgery to minimize complications.

Now I was frightened. What would happen to the class I had just committed to teach in the evening? Could the university cover for me and let me resume after my convalescence , or would they just find someone else? How could my wife and I handle a lengthy disability? My anxiety deepened and the knot in the pit of my stomach grew tighter. I remembered Hanna and her Sisters in which Woody Allen’s hypochondriac Mickey Sachs undergoes in 1986 the tests I was given in twenty years later, for the same type of tumor. My anxious imaginings were no match for the fictional Mickey’s maniacal forebodings, but I could see myself in a wheel chair condemned to life of poverty, pain and immobility. I prayed that my scans would be clean just as his were.

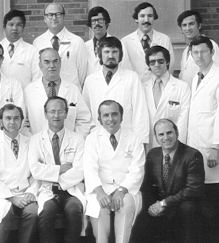

There was hope: Derald Brackmann in Los Angeles specializes in this surgery and has done almost three thousand cases. I knew Derald from my years in research and, I remembered, he trained at Washington University. I even had a group photo showing both of us in our white lab coats in 1972. Perhaps, I thought, the photo would help me persuade my doctor to refer me to Brackmann rather than to someone in St. Louis with less experience.

My fear rose and fell. I kept busy, but stopped for prayer at least every half-hour: “Please God, don’t let this be a brain tumor,” I implored. As an agnostic, I sounded like a hypocrite to myself, praying, but I had to do something to ward off the tumor. Then I thought of death. Why should I die, or not die, at sixty-eight?

Washington University Otolaryngology faculty in 1972. Wally Berkowitz is second from left in the back row. Dave is second from right in the front row. (Photo courtesy of Barbara Bohne, Ph.D)

One morning in the shower, the name Wally Berkowitz came into my mind, from nowhere. Derald Brackmann didn’t train in St. Louis. The young physician in the 1972 photo was Berkowitz, not Brackmann. My link to the perfect surgeon for my tumor evaporated

On my return appointment, I waited in the examination room. From next door, I heard muffled conversation. Was my doctor reviewing my MRI with a colleague, trying to figure out how to break the bad news to me? As the conversation continued, the words became clearer. She was advising another patient about a sinus condition. At last she knocked on the door and came in. “How has your hearing been?” she asked. “About the same,” I said, “and my right ear still feels full.” “We’ll she said, your MRI was normal, with just a few insignificant age-related vascular changes. There’s no tumor.”

Next week: The Robot