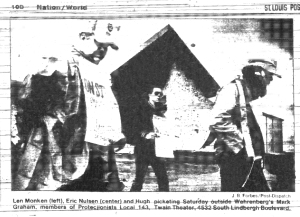

Wehrenberg union projectionists on the picket line in April 1983. The Eric identified in the Post-Dispatch photo was not the same Eric who made all the trouble. Photo restoration be Wally Beagely. In a twist of irony, the building that housed the theater in the background of this photo today is the St. Louis Laborer’s Union headquarters, Local 110.

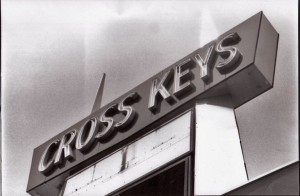

Beginning in mid January 1983, I had resumed my work with the income tax preparation company during the day, running a small office located a few miles from the theater. Around 4:00 PM when the night tax man came on duty, I headed up to Cross Keys, usually munching a fast-food burger while I drove. Like many projectionists, I had a day job, too, at least during tax season. This was my situation when the union walked out on April 2.

The strikers unleashed an array of tactics, tricks and pranks designed to intimidate the public from attending our theaters and to frighten the theater mangers from coming to work. They called me at home at night with death threats in falsetto voices, and once, they called the gas company on my behalf at 3 A.M. to shut of the gas to my apartment building. They ordered a dozen pizzas delivered in my name to the theater one evening. And they argued with customers crossing their line and once laid roofing nails under my car’s tires. I was grateful to the usher who warned me about it.

One of the picketers told my chief usher, Mark, that he and his young colleagues would be safe during the strike. Evidently, a sane voice in the union, fearing ruinous publicity, warned the strikers to spare the high school students who worked at Wehrenberg Theaters and their families from harassment or intimidation. This measure of reasonable caution did not extend to a single mother attempting to support her children by managing the St. Charles Theater from having all four tires on her car slashed.

I changed my home phone number to avoid the harassing calls and asked the University City police to watch my apartment building at night. When the calls continued I learned that Karl, the difficult young usher, had passed my new number on to the strikers.

During the walkout, the drivers who delivered our films in heavy cans each week couldn’t cross the projectionist’s picket line so we, the managers, had to do all the film pickup and delivery in our cars at Wehrenberg’s headquarters after our theaters closed each Thursday night. Our private security guards couldn’t cross the picket line either to escort me to the bank at the other side of the Cross Keys Mall to make the nightly cash deposit, nor could the St. Louis County Police guard our theaters during a labor dispute.

One night, several of the strikers followed me in their cars as I drove to the bank. I feared that they would beat me and steal the money and my car. In truth, I was terrified, even though, looking back, I think that they only intended to intimidate. When they continued to tail me after the deposit, I altered my usual route and they fell back. I repeated my request to the police to keep an eye on my apartment.

They made several telephoned bomb threats to the theaters, usually delivered in Donald Duck or falsetto voices. Ron Krueger, the founder’s grandson and president of Wehrenberg Theaters, brought Gil Kleinknecht, Superintendent of the St. Louis County Police, to speak to a meeting of managers and assistants one afternoon at the chain’s headquarters in Des Peres. Keinknecht, who was a neighbor of Krueger’s, told us how to evacuate theaters and maintain a safe distance with our customers and employees while firefighters and police looked for explosives. He introduced Detective Randy Raines, from the St. Louis County Bomb Squad, who gave us tips on spotting bombs in trash containers and other hiding places.

One night the Donald Duck man made a theater bomb threat to the St Louis County 911 center which recorded it. Our job, Detective Raines told us, when he played the tape individually for each manager, was to identify Donald Duck, if we could. I couldn’t, but David, the drive-in manager, thought it sounded like a striker who walked the Cross Keys picket line occasionally.

In fact, this short and wiry man confronted me once with his dog. The dog growled as I crossed the picket line to enter the theater. The striker said, “He doesn’t like management.” I had to laugh. I had nothing against this man or his dog and understood that he forfeited a much larger paycheck than mine to go on strike.

About a week into the strike, a customer got into an argument with Jerrry, our regular projectionist on the picket line outside the theater. While the customer enjoyed the show, Jerry, an usher told me, went to the man’s car and bent his windshield wipers into a pretzel shape. After the show, the angry man came for me. “Why in hell can’t you provide security outside your theater so these meatheads can’t damage our cars,” he demanded. “I’m very sorry,” I told him. “All I can do now is call the police. Would you like to wait in my office?” A detective arrived to talk with him.

At Cross Keys we usually had only one or two pickets; the union saved its manpower for the drive-ins where they could harass customers by the carload as they attempted to cross their line. The I-270 Drive-in, not far from the Halls Ferry Eight, had large collection of strikers, especially on Saturday nights. One of them was Eric, my regular projectionist, who ranked second only to the Donald Duck man as a troublemaker who tormented both customers and theater managers. In fact, the detective told me, the police planned to arrest him on the I-270 picket line at a time when a large audience of other strikers was watching.

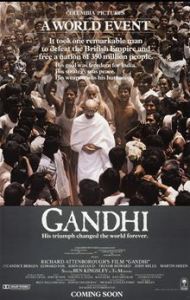

If the union had intended to gain sympathy from the public for their cause, which was to get a better contract from Wehrenberg, they may have figured out that bomb threats, harassment and intimidation weren’t helping. On April 14, 1983, the blockbuster epic “Gandhi” starring Ben Kingsley was playing at the Creve Couer Cinema in central St. Louis County. The strikers staged a march past the theater in Gandhi robes (dhotis) in an attempt to connect their plight with that of the masses of oppressed Indians whom Gandhi had freed from British rule.

“We believe that if Gandhi were alive today, he would tell the people of St. Louis not to cross our picket lines. He was a great supporter of working men and women all over the world fighting for justice everywhere. That’s all we’re asking in this strike—simple justice from Wehrenberg Theaters,” said Mark Miller, Local 143’s spokesman, according to a report in the Post Dispatch. I don’t think that anyone was impressed by the Gandhi march; the stunt did nothing erase the bad taste in the mouths of movie patrons, Wehrenberg employees or executives from the deplorable union tactics that preceded it.

I don’t know if the police arrested Eric. I consumed every spare hour, as I had for the past three years, with the search for a real job, which materialized, at last, during the early spring of 1983. It would be an actual full-time computer programming position for a small St Louis firm which could start me as soon as it got its first check from its client, Jewish Hospital of St. Louis. Besides, the pay would be enough to get me out of debt in a two or three years.

David, who had hired me initially, finally got a real job too during the strike, with a small radio station job in central Missouri. When Julie, one of the assistants who kept up with him told us how much the radio station paid, I joked that David had left the theater business for a profession that paid even less than he earned managing the drive-in.

In the meantime, while my new employer waited for his first client payment, he let me start part-time in the mornings after I closed the tax office on April 15. I find it hard to describe the joy and relief that I felt on my first day at Jewish Hospital, to be treated like a professional who understood technology, physiology and the medical research environment—for the first time in three years. A physician who specialized in computerized measurement spent a full hour with me in a conference room explaining cardiac anatomy and the goals of our project.

In early May the client’s check came through and I visited Wehrenberg’s Manager of Operations in Des Peres to give my week’s notice. Like Paul, my district manager, this man was thoroughly decent and told me that he understood my position entirely. Then he wished me the best.

During my final week at Cross Keys, I gave the new manager, a younger man with more supervisory experience than mine, a quick orientation to the theater. As I passed Jerry, the union man on the picket line for the last time, he smiled. “Dave, I wish you the best of luck, and Eric sends his regards too.”

The drivers license photo taken during my year managing the Cross Keys theater. I had just turned 44.

Later, I learned that the strike was settled on June 11, 1983 to the detriment of the union. The 49 replacement workers were to remain and had to be admitted to the union. The 39 full and part time strikers could return to Wehrenberg only when vacancies arose. Those, like Eric, Jerry and the Donald Duck man, whose shenanigans required the police, were barred from Wehrenberg theaters for life.

The strikers accused Wehrenberg of trying to break the union, and Mark Miller, the projectionist’s spokesman said, “We had no other choice. The public didn’t back us up. We had many union people cross our picket lines to go to the movies.” As for Wehrenberg, its spokesman, labor lawyer John C. Harris told the Post-Dispatch simply that “they did it to themselves.”

A few weeks after leaving, I stopped by the Cross Keys theater to see how things were going. I asked the new manager about Karl, the troublesome usher. “I suspended him for two weeks,” he said. ”He’s fine now.” Paul, the district manager hadn’t objected one bit, contrary to the warning that Sharon, the unpleasant assistant, had given me I tried to suspend Karl several months earlier.

The recurring dreams about the Warwick Theater in from my Marblehead childhood ended shortly after I resigned from Wehrenberg to begin my second career as a computer programmer. Would I like to manage a movie theater again? You bet I would. In spite of everything that happened, it was fun.