The most successful agents had histrionic skills adequate to this task but I didn’t, I realized about a month into the work. Nor was I willing resort to crass manipulations or outright lies, the bullshit part, that my bosses urged on me when my sales were slack, as they usually were. My strong point was listening.

Each week we had a meeting at the office. I got used to the catwalk three stories up; I focused my mind on the doughnuts at the back of the room. Eddie tried to pump us up by congratulating the most successful salespeople for the week. For the rest, he urged us on. “Never go home for the night on a ‘No’, always on a ‘Yes’,” he admonished one day. And then, “Go buy a new car or a new house. The debt will be a great motivator. It worked wonders for me.”

“But not for me,” I thought to myself. What about the six-month’s back rent that I owed and the collection agencies that kept calling?

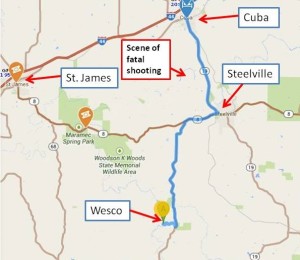

After the meeting I went back to Ben’s office and picked up my new deck of yellow cards. The addresses were in Lincoln County around Troy and Elsbury, Missouri. Some of the people were farmers and some were workers laid-off from factory jobs in St. Louis—The country was in recession. One man, a machinist, was cutting firewood in the forest to support his family. Another had been a boxing champion in the Army years before but had suffered many concussions. We sat in his barn while I listened and he talked and cried.

Some people had problems with their Instant Issue accident policies. When it came to paying claims; confinement at home turned out to be hard to define. We were told just to listen and let the office handle these cases.

I kept a tally of the unemployed among my customers: ten percent just like the country then. Another man, in a trailer park, looked and walked like Toulouse-Lautrec, the artist. He had no legs below the knees from an auto accident in the Navy. Some invited me for dinner. Almost all were warm and welcoming.

As I drove home at night down US 61, I’d turn my dash lights way down and soak in the dark countryside as it sped past. I was at peace, for a while. I had sold a couple of policies but I didn’t feel right about it. I liked these people, and I felt sick when I took their money.

After two months in Lincoln County, the yellow cards led me back to St. Louis. My two small commission checks were nowhere near enough to cover my expenses. In desperation I plunged ahead in spite of the manipulative and dishonest work that I was supposed to be doing. My bosses said that my job was to create the need for our marvelous products, but these people didn’t need life insurance. They needed compassion which I tried to supply in my brief meetings with them.

The card named a single man, but a middle aged couple met me at the door of the house in a St. Louis County neighborhood. He was their son, now in his mid thirties. At age six, they told me, he and a friend had been playing with a gun. The bullet shattered his lower spine and they had cared for him ever since. He wasn’t home that afternoon, but at work. They saw the question in my eyes and explained: He has a wheel-chair equipped van that he drives to his business a few blocks away. He repairs sound equipment for musical groups. They gave me an address.

I found the building, a brick single-family home with bars on all the windows and the shades drawn. I knocked but no one answered. No answer again when I checked back later that day, and again the next. After a week there was a car parked in back and a young man answered the door. He was the business partner of my customer, he said, and offered to show me around. “We’ve had break-ins; that’s why the bars and shades. Druggies like to steal audio stuff.” There were some loudspeakers and amplifiers on the floor of one room, and a small electronics work-bench in another. All the walls in the house were painted black and the other rooms were empty. “He’s not here but you might try his parent’s house again.” I knew that he wouldn’t be an easy sale, but I was determined to track him down anyway. The mother told me to come back the next morning at eleven; her son should be out of the shower by then.

His special van was parked in the driveway when I got there. “He’s in his room dressing but he doesn’t want anyone to see him,” the mother said. “You might talk with him through the door.” I had burned almost two weeks trying to find this guy, so I knocked. “Yeah, who is it?” I introduced myself and gave him the canned sales pitch through the closed door. “No, I don’t need anything like that,” the voice came back. My job was done.

I made a couple of sales calls in Valley Park a few days before Christmas, 1981 and one or two afterwards. I went to Thomas, my boss, and said that I was quitting. “We were thinking that it might be a good idea, too,” he said. He wished me good luck.

A year later I was managing a movie theater in a St. Louis suburb, one of the Wehrenberg chain, with two screens. I didn’t get to choose the movies that we ran; booking was done by the central office. So when my boss told me that we would be showing “Bloodsucking Freaks,” I asked him to repeat the title. We both laughed, but I knew better than to question this choice. Maybe some other theater would get the next turkey that our chain had to take in its booking package. “Freaks” was a grade-D movie that belonged in a porn house or in a rural drive-in somewhere. Maybe eight people bought tickets to see this deplorable epic during the week that we had it. I watched about five minutes: several naked women were cannibalizing some guy in a prison cell. That was all I could take.

I came out of the storeroom one evening and thought I saw the back of a motorized wheel chair disappearing into the “Freaks” side of the house. I had a hunch and sat in my office until the show started. Then I took a tour of the parking lot and there it was: the wheel-chair van that I had spent two weeks pursuing when I was trying to sell life insurance.

I was busy counting receipts so I didn’t him leave the theater. A week or two later, I saw on the news that he and his partner had been arrested for selling drugs, big-time, out of his business and from the van. The news showed a shot of the house with the barred windows. No wonder he didn’t want to meet me. I could have been a cop.

About four years after I quit Penitential Life, I talked with a man I’d met a couple of times. He was a salesman who had sold everything from encyclopedias to Fuller brushes, all door-to-door cold calling.

“Yeah, I worked there too,” he said, when I mentioned my adventure in life insurance sales. We talked about Sam, the licensing teacher and how good he was. I asked about Eddie, the boss at the agency. “His wife got sick and you know he had their health insurance with Penitential Life.”

“Of course, who else?”

“Guess what? They reneged on his claim. Just about tore Eddie up. A few months later, he’s dead from a heart attack. Not even forty-five.”