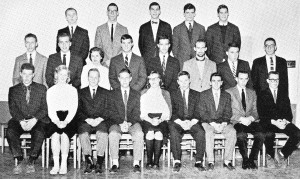

The WRMC staff in 1960. Back row: Gary Hoover, Dave Martindale, Ron Wysocki, Pat Parsons & Chris Baker.

Middle row: Dave Hulihan, Dave Crowley, Leelaine Rowe, Fred Busk, Frank Sutherland, Conrad Wettergreen, Phil Clickner & Pete Leone.

Front row: Joel Pokorny, Lorrie Kittredge, Ed Rothchild, Mike Marcus, Marty Chamberlin, Greg Nagy, Dave Rubenstein, Jeff Entin & Mark Skolnik

Over the summer of 1958, the College tore down the Student Union for replacement with a new structure. They built a temporary studio for us in a small building on campus, Recitation Hall, where we continued to produce some programming. Our hearts weren’t in it, though, because we knew that few dorms could receive our signal. Nonetheless we continued to cover out-of-town sports events. Middlebury College was a major power in collegiate hockey and one our strongest competitors was St. Lawrence University in upstate New York. I was on duty with another staffer at the studio the night of the St. Lawrence game in the fall of 1958. We were anchoring the play-by-play which came over a leased phone line from Canton, New York. Suddenly the feed from the hockey game went dead. We couldn’t communicate with our reporter at the game; we just had to fumble with every control we could find in the studio and attempt to reach the phone company to check on the integrity of our line. At this point, the president of Middlebury College, Samuel S. Stratton walked in. Just like the others who gathered in the studio to hear the game when they couldn’t receive it at home, he wanted to follow the excitement of one of our most important contests. I was terrified because I would have to explain the technical problem to him. Instead of the explosion and summary expulsion that I feared, he said that he understood and might try back later.

After flunking out of college in mid-sophomore year, I spent the spring and summer semesters of 1959 at Boston University as a night student, working during the day. When I returned to Middlebury in the fall of 1959 as a junior, construction of the new student union building to be called Redfield Proctor Hall was well under way. Dave Hulihan, a classmate headed for a career in architecture, took me on several tours of the new building after the workmen had gone home for the day. He pointed out every detail, from the steel studs that had just come into use, to the flexible “Modernfold” doors that separated sections of the dining hall. When we could get into the basement, we visited the new WRMC studios. They occupied the same relative position—the northwest corner—that they had in the old building. The last time we saw them before completion, the studios were just at the stud stage.

By this time the station had been off the air for over a year. I don’t remember how we kept this student organization going during this tough period. There was a lot of conflict among staff members, but some strong personalities emerged. Chief among them was my junior year roommate Ed Rothchild and two women in my class, Lorrie Kittredge and Leelaine Rowe. I had been burned in the infighting and decided to remain on the sidelines for a while until things calmed down. Our spirits lifted when the college showed its commitment to WRMC by building the new studios that Hulihan and I had toured. But new quarters wouldn’t fix the transmitter problem.

Our FCC license restricted the range of our broadcasts to the college campus; any external antenna that could reach all the college buildings would also project our signal into the town of Middlebury, as our predecessors had learned in 1950 when the license was suspended. Someone in the college administration, or in WRMC’s student leadership, had the good sense to contact John Bowker, Jr., the station’s founder at RCA’s David Sarnoff Labs, in Princeton, New Jersey, where he worked.

Bowker and one of his technicians designed and built a number of small transmitters, one for each college dorm, that would attach to the electrical wiring and carry the radio signal throughout the building but not beyond. The college covered Bowker’s expenses and provided dedicated telephone lines from the new studios to the electrical panels in the basement of each building. One weekend in 1960, before the opening of our new studios, Bowker and his technician came up to Middlebury to install the new transmitters, comprising what they called a carrier current system. I watched the installation in Starr Hall, one of Middlebury’s oldest buildings, where we had to stoop to move about in the cellar.

Back row: Bill Custard, Lorrie Kittredge, Jim Dreves, Mary Hart & Dave Gannett. Front Row: John Wallach, Mike Black, Ed Rothchild, Pete Frame & Pete Leone

It went quickly. They removed the cover of one of the electrical panels, attached a couple of wires, screwed a bracket for the transmitter onto a wooden board, ran another wire to the telephone jack, and took a reading on a device known as a field strength meter. They replaced the panel cover and moved on to the next building.

With new studios and a signal that could be received fairly well in each dorm, WRMC prospered. Many talented students joined the staff, while I withdrew to focus on my studies, and on a new set of friends among the psychology students who, like me, were headed for graduate school. Three days a week I did a morning newscast and then went upstairs for breakfast in the new Proctor Hall dining room, where, if I was lucky, I would find one of my friends.

Next week: Insomnia