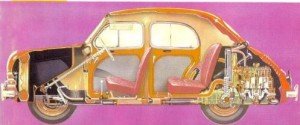

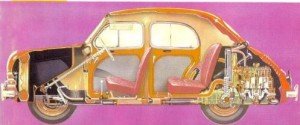

A 4CV displays its rear engine and front trunk.

“Dave,” Jack said as he lifted the rear hood to reveal the engine, “the 4CV is easy to work on and so light that you can pick it up by the front bumper if you need to. But you have to go the Renault dealership in Boston for parts, unless you have another 4CV to cannibalize. The cars are dirt cheap used.”

It was spring, 1956 and I was 17. I had just earned my driver’s license and wanted my own car which I was determined to pay for myself. I wasn’t about to burden my parents and the car, like the fancy bicycle before it, would come from my own after-school earnings. Jack was an engineer, a family friend in his fifties who loved to tinker. I spent some Saturdays with him, handing him tools as he worked on his cars and on a boat. I drove the 4CV, first with him and then alone. It was light, simple and easy to handle. Everything was manual: the starter was a lever you pulled up; the choke was tricky and required careful adjustment during warm-up, and the transmission had a gearshift on the floor with a clutch pedal. There was even a crank with a slot in the rear bumper, if you had trouble starting. The stick shift and choke were not a problem. I had learned to drive on cars with both. As for the crank, my father knew all about them; he had learned to drive in a Model T.

Jack had a colleague, Dave, who was selling a used 1949 4CV. My parents drove me over one evening for a look. The car was a faded blue and had couple of dents, but it ran OK when I drove it around. He agreed to sell it for $125 and I gave him a $25 to hold it while I took care of insurance and registration.

Most of my teenage friends drove on their parent’s insurance, but I wanted my own. Massachusetts insurance companies wouldn’t insure teenage drivers directly; you had to go through an assigned risk pool, which involved visiting an unfriendly office in Boston. The Registry office in Lynn was just as bad. The clerks there, like the ones in Boston, knew from the news that every teenager coming through the door was a violent juvenile delinquent who would wind up killing someone if they were allowed to drive, much less register their own car.

With license plates, windshield stickers and insurance arranged I asked my father to drive me over to Dave’s. The blue 1949 4CV was sitting outside his apartment building just where I had seen it before. I handed over $100, collected the keys and got in. But now there was an odor that I hadn’t notice before. It was the sour musty smell common then to all used cars beyond a certain age. The new-car aerosol spray employed by used car dealers had yet to be invented, or if it had, it was not for 4CV aficionados. If you were tough enough to take on a 4CV, you shouldn’t be bothered by a little odor. It didn’t trouble me a bit. I was delighted. My car ran and it was all mine: bought, paid for, insured and registered.

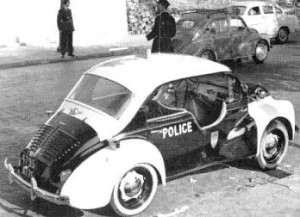

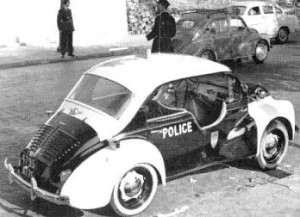

The 4CV in “Afrika Korps” yellow

In my spare time, I drove it all over Marblehead and on trips to Salem, Danvers and Beverly. I picked up a bulky AM radio at a junkyard and installed it myself. In my fantasies I always wanted to drive a police car, so I installed a small war surplus flashing yellow light on the dashboard facing out the front window. One day, in the summer of 1956 when I was driving on Essex Street in Marblehead a group of my friends approached on foot. Inspired by the clowns in the circus, four of them opened the doors of my still moving car and squeezed in. The fifth climbed on the roof and pulled himself forward until his head hung down and his face appeared through the windshield, upside down, looking directly at me. I was horrified. Not only was my view blocked, but my friend risked serious injury or death if I stopped too fast and flung him in a neck-breaking somersault to the pavement. Traffic was light,no police were around and I was able to slow for a safe dismount.

In late August 1956 I felt confident enough to take my car on a short camping trip to New Hampshire with a couple of friends from Boy Scouts. I had doubts but the little car made it up and back with no trouble. But in the fall it became less and less reliable, often stalling in the middle of intersections. It was light enough that I could jump out on a level street, push it a little, and jump back in to pop the clutch, using the car’s mom entum to turn over the engine. If jump-starting didn’t work, I still had the crank, which, at least for a while, got it going again.

I took it to Jack, who had recommended the 4CV in the first place, for help. But he got tired of my constant requests, and to ld me that I should be able to fix it myself by now. I turned then to one of my Boy Scout companions, Billy, who had greater mechanical abilities than mine and enjoyed challenges. After several trips to Boston for parts he and I got it running for short periods, but then it would die again. My car sat for weeks at the curb near our house. An uncharitable neighbor left an anonymous note on the windshield threatening to call the police if I didn’t move it. I continued to fiddle with it, cranking the engine over and over. Nothing I did would make the recalcitrant machine start. In anger and frustration, I screamed and beat the valve cover with the crank until I dented it.

Billy and I came up with one final idea. We would tow the 4CV with a strong rope attached to his car, and maybe build up enough momentum to jump-start mine. We found a hill and he slowed his car to create slack in the towrope while I popped the clutch. Nothing doing. We tried again on a flat stretch going about twenty miles an hour. Again, no luck. I told my mother about the outcome. “You’ve got to do something about that car,” she said, “I can see that the frustration is tearing you apart!”

The next day Billy drove me over to Litvak’s auto salvage on Bridge Street in Salem, where I had found the old AM radio. Litvak offered to tow the 4CV from Marblehead at no charge if I’d turn the title over to him. His tow truck followed us Marblehead and I went into the house to get my mother’s signature; at eighteen, I was still a minor. “Are you dead sure that this is the only solution,” she asked. “I don’t see any other and the tow truck is waiting outside,” I said. He put my car on the hook and we watched it disappear around the corner. Soon after, my mother and I drove past the salvage yard and I saw the 4CV out in front, offered for sale as running. I wondered what Litvak’s mechanics had done that neither Billy nor I or could manage.

The idea of the 4CV originated in the mind of Louis Renault, a French manufacturer of large luxury cars. Renault was impressed by Ferdinand Porche’s 1938 introduction of the German people’s car, the Volkswagen, and began the development of a French equivalent. He was under way when the Germans invaded and took over his plant in suburban Paris for the manufacture of trucks. Working out of sight of the Germans, Renault’s engineers to produced a prototype of a small inexpensive car in 1942, but kept it hidden.

At war’s end, in 1945, the French Government arrested Porsche on charges of war crimes; he had managed automotive factories in France during the occupation. They required him to lend his expertise to the Renault project, but he complained that his involvement came too late to make a difference. But the rumor spread anyway that Porsche had undermined the reliability of the French automobile in revenge for his imprisonment. His son bailed him out and he was never tried by the French or anyone else.

In 1946, Renault introduced its new product, the Quatre Chevaux à Vapeur (4CV) which means four horsepower. All the initial cars, first marketed in 1947, were a sandy yellow color – the result of a huge surplus of automotive paint intended by the Germans for use in the North African campaign. The 4CV was very successful, and spread rapidly through France and its possessions. Soon it, along with the postwar Volkswagen, was available in the United States. Renault manufactured the 4CV until 1956, when it redesigned it with a new body style and called it the Dauphine. The Dauphine was even less reliable than its predecessor. Nonetheless, quite a few sold in the United States, including the car belonging to a college acquaintance. He liked his Dauphine and didn’t seem worried by my experiences with the 4CV.

The 4CV demonstrates its versatility

One Saturday late in 1999, forty-two years after I gave up on my 4CV, I tuned the radio to “Car Talk” and found Tom and Ray Magliozzi sponsoring a competition to select the ten worst cars of the millennium. I thought of my first car, but by 1999, it faced lots of competition for membership in the pantheon of automotive unreliability and lethal handling. As it turned out, the 4CV didn’t even rate a dishonorable mention in the ultimate ranking. But Renault made the cut with the Dauphine in 9th place and “Le Car,” a later automotive disaster, in 6th. First rank went to the Yugo.

Next week: Dave encounters computers.