In 1950-51, when I was twelve and in the sixth grade, we lived with a family friend I’ll call Jean. She owned an advertising agency with offices in the Pickering Coal building in Salem, and had recently bought the Victorian house at Eighteen Pearl Street in Marblehead. Our landlord at Twenty Circle Street wanted his house back on short notice, and Jean had two large extra bedrooms. We moved in just after school let out in May 1950.

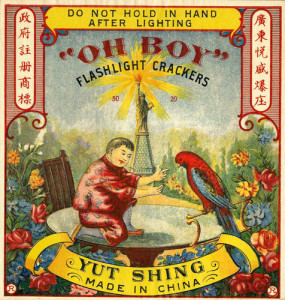

Like other boys in the days before drugs, I found all the excitement I needed in a non-chemical adventure just as dangerous: playing with gunpowder that we salvaged by scraping dozens of paper caps intended for toy pistols, or from the occasional firecracker that we scrounged. Fireworks were illegal in Massachusetts, but as the Fourth of July approached most kids my age got their hands on a few firecrackers, either from family trips to the south where they were sold in roadside stands, or by mail order. Mail order fireworks were tricky. The vendors wouldn’t ship to states where they were illegal, but they did ship to New Hampshire, which had less restrictive laws than Massachusetts. Many Marblehead families had friends and relatives in New Hampshire, but I didn’t.

I was describing the fireworks dilemma to Jean, one day, when her face lit up. “There’s a man where I work, Ralston Pickering, who gets his fireworks by mail order in New Hampshire. I’ll see if he can get some for you.” The next day, Jean came home with a fireworks catalogue. I was delighted but didn’t really believe that the scheme would work: this Ralston Pickering guy would forget my part of the order, or he’d be stopped by the State Police when he returned to Massachusetts. I went ahead anyway and ordered a modest collection including several packets of ladyfingers, tiny half-inch firecrackers that you set off by the whole packet, even more packets of the one-inch variety which were the favorite of all the kids, a bunch of sparklers and a few small rockets.

After two or three weeks of anxious waiting, Jean announced that Pickering would bring my order to work the following day. Jean brought the small carton home, and I raced upstairs to my room to inspect my cache. I couldn’t wait for the next day to tell my friends, Chris Brown, Tommy White and a boy I call Tim about what I had. Setting them off by myself held no appeal; I had to share to enjoy them at all.

I kept the box in the blanket chest below the window in my bedroom and gave the fireworks to friends as the Fourth approached— with the understanding that we shoot them off together. We did, mostly in the back yard at Eighteen Pearl during the daytime when we wouldn’t attract attention, or the police. We even fired off a couple of rockets there and had no idea where the hot debris landed.

Kids who wanted to set them off by themselves or with others had to pay me cash, I decided. After all, It added a little cachet to my otherwise powerless existence. I sold the final half-string of one-inchers individually for a quarter each, except for the last two or three which I sold to Tim for fifty cents each.

The association of New Hampshire with fireworks lay submerged in the recesses of my mind along with other childhood exploits and misadventures; I hadn’t thought about it for over sixty years. Then I read of the indictment of Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, one of the two brothers accused in the Boston Marathon bombing that killed three people and injured more than two-hundred others on April 15, 2013 Tamerlan, the deceased older brother, had visited Phantom Fireworks in Seabrook, New Hampshire in February and bought 48 mortars, which, the indictment alleged, the two of them used to construct the pressure cooker bombs that they detonated at the marathon’s finish line. It seems that fireworks laws in New Hampshire hadn’t changed much. Just like us at age twelve sixty years ago, they had salvaged gunpowder from ordinary fireworks.

We moved from Eighteen Pearl in the summer of 1951, just before I started junior high school. Jean sold it a couple of years later and eventually moved to Florida. The house looked shabby when I walked by during my high school years, but now it is restored to its delightful Victorian splendor.

Next week: Freddy at Eighteen Pearl