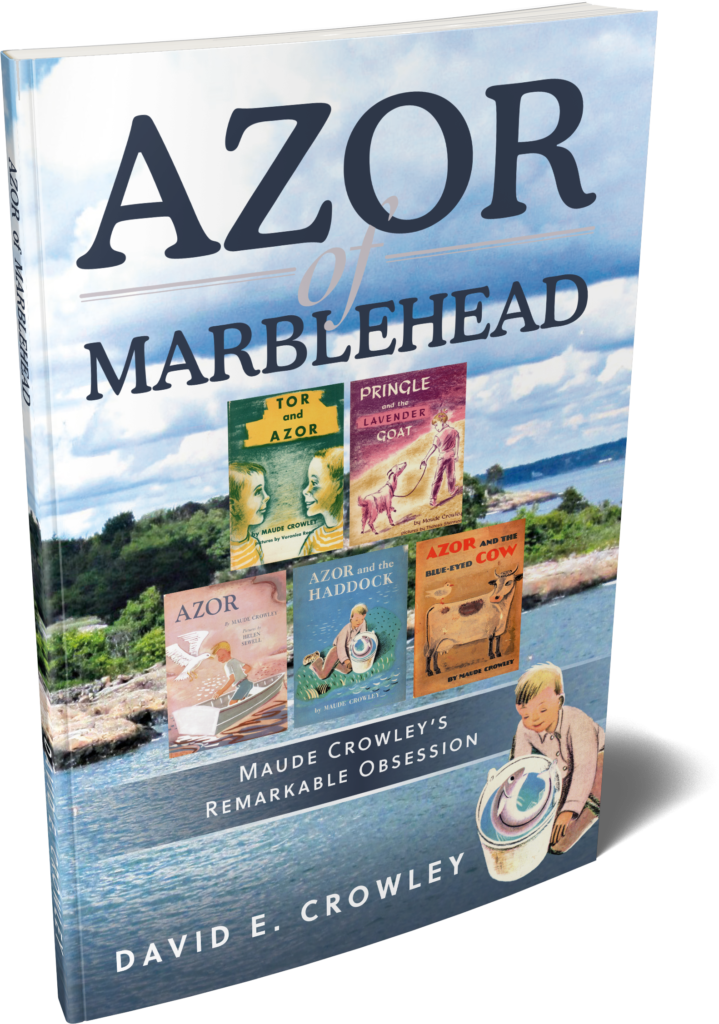

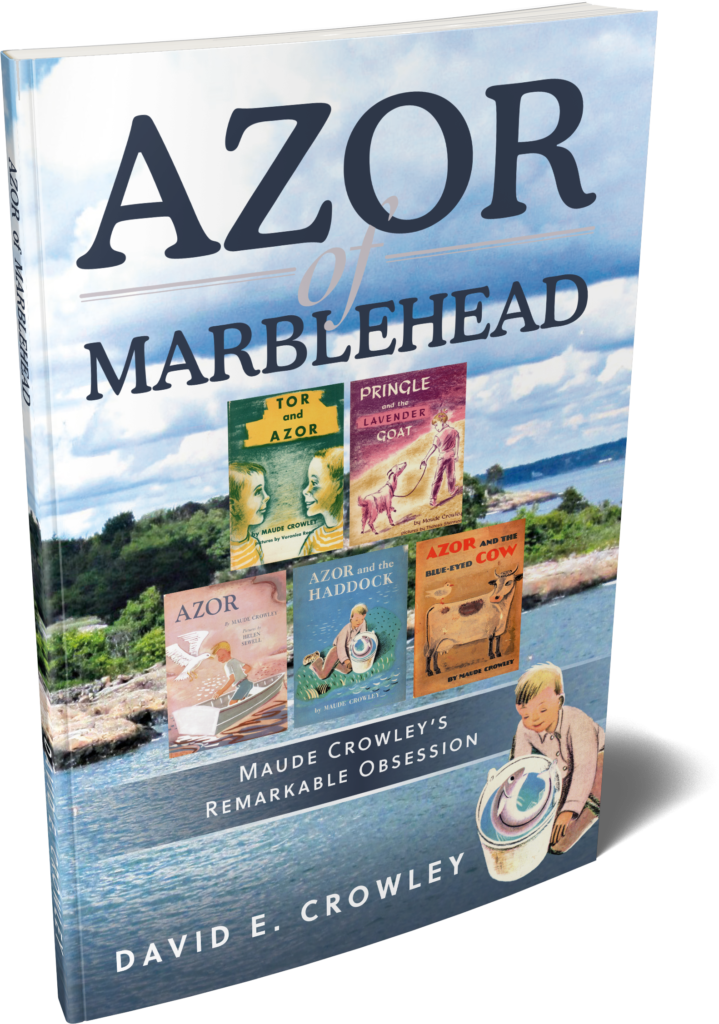

Contact dave@davidecrowley.com to order at a hefty discount from the original price of $21.95! Now $14.95 including priority shipping

Check out the synopsis to learn more:

Contact dave@davidecrowley.com to order at a hefty discount from the original price of $21.95! Now $14.95 including priority shipping

Check out the synopsis to learn more:

Thursday (July 23) evening the Marblehead Museum featured a presentation about my new book Azor of Marblehead introduced by museum director Lauren McCormack. Here’s the Youtube link: https://youtu.be/DFNF5OIG2VQ There’s also a link on the Museum’s Facebook page to the general meeting which preceded my talk: https://www.facebook.com/Marbleheadmuseum/videos/292690558738659

Right now the printer, Graphic Connections Group, is sold out of my book. I’ve ordered a second printing which should be ready in a week or so. In the meantime, you can pre-order from the Marblehead Museum at this link: https://marbleheadmuseum.org/gift-shop/ When the new copies ready I’ll go the printer and sign a bunch copies for you, and I’ll ship a new supply to the Marblehead Museum. Of course, I’ll let you know when this happens.

Join us on Thursday, July 23rd at 6:30 PM Eastern (5:30 PM Central) (members meeting) followed by a presentation by David Crowley on his recent book. Dave Crowley, son of Maude Crowley, will present a talk on his book Azor of Marblehead the story behind the famed children’s series written by his mother, Maude who sadly passed in 2000 at age 93. The books were published between 1948 and 1960 and were treasured by adults for their warm evocation of unique Marblehead characters, for their humor, and the wit & intelligence of the boy Azor himself. Children read them in Marblehead schools; some producing drawings based on scenes in the books. Meeting is via Zoom and is FREE. Register here: https://form.jotform.com/201883897103158

Henry Baay’s Yacht Yard in Marblehead from a 1930s postcard. Photo courtesy of the Marblehead Historic Commission.

Henry Baay was not popular in Marblehead, Mass. when I was a kid in the 1940s. An immigrant from Holland, he owned two boat yards, one off Lee Street (where the apartments are now located) and one in Little Harbor. If he caught you playing around his boats or swimming off his docks, he’d chase you for several blocks and even further if you called him rude names

Chris Brown and I often cut through his Little Harbor boatyard on our way to Gashouse beach or to other boatyards. At age nine, we loved to play in the old boats or just watch yard operations. During workdays, we didn’t linger in Baay’s for fear of being caught by him. Other yard owners didn’t mind if you watched from a respectful and safe distance, but not Baay. He’d come after you. He looked like an old man, but he was very quick on his feet.

The derricks in his Little Harbor yard were anchored at the base near the corner of the largest boatshed. One Saturday, when no one seemed to be around, Chris and I untied the ropes hanging from the top of one of the derricks and began to swing the long high wooden boom back and forth. Baay, who had been working in his second floor office came out to see what was going on.

Henry Baay at the helm in this Leslie Jones photo from the collections of the Boston Public Library. Jones worked for the Boston Herald Traveler from 1917-1956.

Chris escaped, but Baay, with white hair and an open shirt, grabbed me by the arm and dragged me upstairs to his office where he told me to sit by his desk. I was terrified. I knew how mean he was and had no idea what he might do to me. He asked my name and opened the telephone book. He got my father on the phone:

“Do you know that your son here placed himself in great danger by playing with the heavy derricks in my boatyard. If one of then fell he might have been killed,” he said in his harsh-sounding, crackly and accented voice.

Then he turned to me:

“Now go home and don’t let me see you playing such risky games again.”

The fear drained out of me, as I ran down the stairs and out of his yard.

Baay’s reaction to kids playing in his boatyard may have come from worries about liability in case a child was injured or killed. His unfenced facility with it derricks and open docks might be judged to be an attractive nuisance, and he might have to pay, or worse, lose his boatyard and boats, to say nothing of the anguish he would suffer. Why other boatyard owners facing the same risks didn’t react as he did was likely a result of their different personalities. Baay seemed disagreeable and harsh.

Henry Baay at the helm in the Bahamas, from Boats, Boat Yards and Yachtsmen (Van Nostrand, New York, 1961)

Four years after my run-in with him in 1948, he sold the Little Harbor yard to a pleasant and friendly man named Dick Price who had no problems with kids in the boatyard. Baay converted the Lee Street yacht yard to a modern apartment development which he managed for maybe a decade more. Later he wrote a book about the problems of boatyards and yacht ownership, and retired to Florida. He acquired a yacht, the Trillium, which he sailed in the Bahamas during his last years. He died in Fort Lauderdale in 1975 at age 71, after battling cancer and heart disease.

For anyone who loves boats and the sea, Baay’s book Boats, Boatyards and Yachtsmen (Van Nostrand, New York, 1961) is a well-written and fascinating compendium of nautical expertise. He wrote before fiberglass had replaced wooden hulls on most recreational yachts, but his expertise on buying and selling boats of any kind holds today and must be respected.

When I arrived home in 1948, still shaking from my encounter with Baay, I expected my father to be angry, but he wasn’t. He wanted me to be careful, of course, but he pointed out that he had played in the railway yards in Salem when he was a boy my age, and had fallen off the top of a freight car.