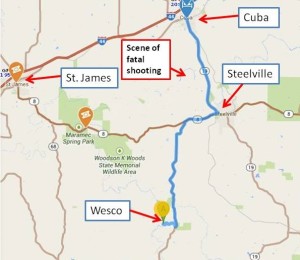

Map showing Wesco where Dave came under fire in 1973 and the scene of the 2013 shooting near Steelville

When I was 34 and recently divorced, a graduate school friend, Jim offered to take me fishing. An ardent angler, he had explored much of the Upper Meramec River south of Steelville, Missouri to find the best locations. I bought a cheap spinning rod, some lures and a tackle box and equipped myself with a fishing license. Jim took me to a spot just beyond the tiny village of Wesco in the southern reaches of Crawford County. Here the dirt road crossed the narrow river on a concrete slab, providing easy passage at low water.

We pulled off and parked in the grass. As we walked upstream along the east bank Jim cast his lures into promising pools visible from the shore. The riverbank was narrow, constrained behind us by trees and thick brush, and in places we had to wade in the river get through. Jim was hoping for bass or catfish, but had to settle for a few crappie.

We came to a place where the river turned and widened. Jim pointed to some whirlpool flows near the opposite bank. “That’s a deep spot, where bass and catfish like to hide,” he said, adding that we could probably wade halfway across to make casting into this pool easier. We did, but my lure snagged in the pool, because I was less experienced than Jim. “Sometimes property owners along the river sink old bed springs into these pools to frustrate fishermen. They consider the whole river to be their private property.”

I had a girlfriend, Billie, with two daughters, Angela 10, and Erin 8. A couple of weeks after my trip with Jim I offered to take them down to Wesco to enjoy the river and maybe catch some fish. We parked where we had before and I led them along the bank to the spot with the deep pool. We waded out to get closer to the pool at the bend in the river. Then I heard something that sounded like a man shouting. I looked up and saw on the western bank of the river a lawn with a house at the back. I couldn’t make out what the man who had come out of the house was saying but I saw that he had a rifle. Unsatisfied with our lack of response he fired some shots into the air.

I told Billie and the girls to get down and we crouched and beat a retreat into the thick brush beyond the eastern bank. I listened for the sound of bullets crashing thought the trees above us but heard none. I was scared but focused on getting us to safety. We cut through the brush on a zig-zag course back to the car and I drove to the Crawford County Sheriff’s office in Steelville, the county seat. It was maybe 4:30 on a Sunday afternoon when I opened the door to find a thin young man sitting at a desk with a radio dispatch console.

“The sheriff isn’t here; I’m his son and I’m just filling in as a dispatcher.”

I told him our story. “You shouldn’t have been there,” he said. “It’s private property.” I was dumfounded by his response. I had seen no signs forbidding trespassing. I said, “What?”

He continued. “That’s a well respected family from St. Louis who come down here on the weekend to enjoy their property. They’re entirely within their rights to drive trespassers off.” “Who are they?” I asked. “I can’t tell you that,” the young man replied. I was still shocked and said nothing as I returned to the car. All sorts of thought raced through my mind; the first was that the young dispatcher would be singing a different tune of one if the children had been shot by this guy, and other was that it’s OK to shoot at women and children in Crawford County.

Monday morning I called Ben Roth, the attorney who had handled my divorce. He said that Missouri had never defined property rights in rivers and streams. Some owners consider the whole stream, including the opposite bank to be theirs. The guy we had encountered must have held this belief because he was still shooting as we reached the bank opposite his property.

All of this happened 41 year ago, in the summer of 1973. I never went back to Wesco nor did I take anyone fishing on the upper Meramec again. I didn’t have time to research Crawford County property records to determine the name of the man who had threatened us with gunfire.

The Meramec at Wesco is not easily floatable in low water, but that’s not the case 28.6 river miles north near Steelville, where it’s good deal wider. It was there in August 2013, that a man, James Crocker, shot and killed Paul Dart, Jr. a member of a large canoe-float party. It’s clear from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch’s coverage that many canoe-float parties involve a lot of drinking and pot-smoking. Property owners along the river get tired of trash and human waste left by drunken floaters.

Given my experience with Billie and the girls, I wanted to know how law enforcement in Crawford County would handle this new case. The circumstances were different: to any observer, we had looked like a family with two children simply wading in the river. Dart’s group included nearly 50 people and some were intoxicated. They stopped at a gravel bar and one of them walked into the woods to urinate. Croker appeared with a 9-mm handgun and told them to get off his land. When they didn’t budge, he fired a warning shot next to the man who was relieving himself. Then other floaters reproached Crocker and a dispute arose over the ownership of the gravel bar. One of the floaters, not Dart, picked up a rock and Crocker shot Dart in the face. He died in an ambulance on the way to a hospital.

Had things changed in Crawford County in the 40 years since our incident? Apparently so. The press and TV news supplied extensive coverage, and on Sunday, the day after the killing, the county prosecutor, William Seay, charged Crocker with second-degree murder along with several other violations The trail began on Tuesday, May 13, 2014 and the jury took only two hours to convict Crocker of second-degree murder. Crocker’s defense rested on his claim that the floating party was trespassing on his land, but a surveyor testified that Crocker’s property line was 381 feet from the gravel bar where the shooting took place. A self-defense claim by Crocker was rejected by the jury who recommended a sentence of 25 years. All 59 of the 60 potential jurors admitted to owning firearms, but the panel of twelve jurors selected sent a message by their finding, that you just can’t shoot at people who you believe to be trespassing. I wish that sentiment had prevailed 40 years ago when I visited the sheriff’s office in Steelville.