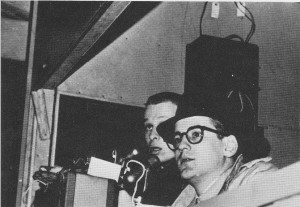

John Bowker, Jr. working with a student at the second radio station he built at Tennessee State University in 1971

Right after my first visit to the WRMC studios I went back to my room in Painter Hall to tune the station in. There it was— a little scratchy but clear— coming out of my little AM radio. This was a true wonder, I thought, to hear the sound of a radio station I just visited in person and to hear the voice of an announcer I met less than an hour before. Some evenings when I wasn’t at the studio running the controls, I’d tune the station in from my dorm, but the signal would be very scratchy and sometime even unintelligible. How could this be, I wondered, for a radio station with studios less than three hundred yards away?

It turned out that students in other dorms were having the same problems. We had many discussions with our chief engineer, the upperclassman I’m calling Marty. To start with, he said, the FCC limits college stations to very low power to avoid interfering with other stations, particularly at night. Using the underground class bell wiring as an antenna was intended, in part, to limit our signal to the dorms and classroom buildings right on campus.

The station had first gone on the air in May 1949, broadcasting from a chicken coop, or so we believed, in the backyard of John G. Bowker, a professor of mathematics who lived in a small house adjacent to the campus. Bowker’s son, John D. Bowker, was the student who built the first transmitter which was connected to some kind of antenna. Young Bowker was an amateur radio operator who went on to a brilliant career as a broadcast engineer with RCA. He could not have been responsible when another student connected the transmitter output to a chain link fence to improve the coverage of the station. It worked, but the signal escaped the bounds of the campus, reaching a radius of ten miles around the Town of Middlebury and leading the FCC to suspend WRMC’s broadcast license, all according to a history of the station written by Don Kreis in 1981.

Some knowledge of this background figured into our discussions of the coverage problem we had in the fall of 1957, but we didn’t know details because the founders of the station had long since graduated. We didn’t even know if the dust covered transmitter with glowing tubes in the back room next to the teletype machine was the original one built by John Bowker, or something concocted by a successor.

Marty told us that replacing the transmitter would go long way toward improving our signal, but that the other part of the problem, the underground bell-system wiring that we used as an antenna, was beyond our control. That part of the system was the domain of the college’s Department of Buildings and Grounds (B & G) which we, in our student paranoia, believed to be an enemy of WRMC, not through deliberate intent, mind you, but from gross, overwhelming incompetence. B & G’s director, we believed, was a product of the Brandon Training School, just south of Middlebury, which used to be called the “Brandon School for the Feeble Minded.” This name fit the man in charge of B & G perfectly, or so we thought. He was, in our opinion, a true moron who allowed his crews to cut the underground bell system wiring whenever and wherever they felt like it, without the slightest regard for our precious radio signal. Of course we knew nothing of the B & G director’s actual qualifications— that he held an engineering degree and that he was licensed by the State of Vermont as a Professional Engineer.

Not only did our silly paranoia prevent us from approaching this man who could have helped us, I’m sure, but it also blocked our approach to Professor Bowker who could have arranged for his son at RCA to consult with us, or to Ben Wissler, the Professor of Physics who could have supplied expert technical advice. Instead we decided to build a new more powerful transmitter which Marty would design and that he and I would build.

The best electronic supplier for our needs, Marty told me, was located in Springfield, Mass, a two hour’s drive west of Boston and about four hours south of Middlebury. The plan called for us to return early from spring break, stopping on our way in Springfield to pick up the electronic parts, and then driving in Marty’s station wagon on up to Middlebury. This we did in April, 1958 after informing the college that we’d need our dorm rooms for a few days before the rest of the students returned for the resumption of classes..

The new transmitter was to be housed in a large standing steel cabinet, about two-thirds the size of a telephone booth, that we assembled in WRMC’s back room under the Student Union. Called a relay rack from its origins in the telephone industry, this cabinet would accommodate standard-sized panels, shelves and even a back door. Parts of the new transmitter would rest on shelves at various levels, beginning with the power supply on the bottom.

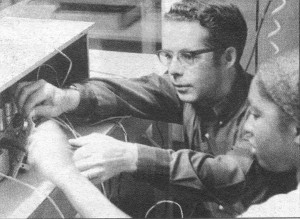

Marty introduced me to the basics of electronic construction which began with punching appropriate sized holes in blank aluminum chassis for radio-tube sockets and a host of other components. There were lots of holes to drill, wires to strip to remove insulation, and numerous connections to solder. As we progressed he showed me the proper technique for each of these operations. After a couple of days we had the power supply built and had installed red indicator lights and meters on the front panel. Classes resumed soon after the power supply was completed. With our divergent schedules Marty and I couldn’t work together any more. Marty, with electronic knowledge far superior to mine, had to finish construction of the new transmitter on his own. In the meantime WRMC was off the air.

Considering my terrible mid-term grades I was determined to put more effort into my classes, which I did, at least for a while. I missed the debut of the new transmitter, but turned on the radio in my dorm room the next day to check the new signal. WRMC’s spot on the dial was dead silent. I ran down to the studios to find a group of glum-faced staffers: everything had gone fine at first, but in early morning of the second day, a coffee shop employee had noticed smoke seeping out from under the door of WRMC’s transmitter room. A college electrician investigated and traced the source to our new transmitter which he unplugged. I don’t know what went wrong with the circuits that Marty and I had built but the college wouldn’t allow us to repair it. We had to go back to the old machine.

Next week: WRMC Revived