When I was a kid, I dreamed of becoming an aeronautical engineer and an officer in the Navy serving on aircraft carriers. My high school grades in math and science, a mixture of B’s and C’s, should have been a tip-off that engineering wasn’t a good plan, but I ignored them. I also minimized my rejection for a Naval ROTC program that would have paid for my college, and given me a commission at graduation. Mere obstacles to be overcome.

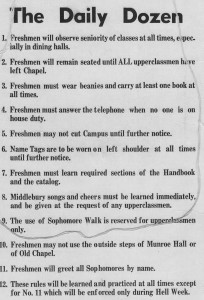

When MIT and other top colleges rejected me I began to worry. “You might consider a three-two program,” the MIT admissions officer said, “Do well for three years at certain schools and MIT might take you as a transfer student.” That’s how I turned up in the fall of 1957, at age eighteen, at Middlebury College in Vermont

College was a shock. Compared to most other freshmen, my social skills were right in line with my athletic abilities: close to zero. Fraternity rush was a nightmare — no one wanted to talk with me, and I ended up by default in a non-affiliated men’s group, called the Atwater Club. The B’s and C’s of my high school years sank to C’s and D’s in college.

“Lots of people have a rough time in their first year of college and turn out fine,” one of my parent’s friends assured me. My parents themselves were all encouragement, too, without a word of criticism, bless them.

I hung on to my engineering dream and returned in the fall of 1959 for another go. I moved into the Atwater Club off campus. The other guys were misfits like me, some very intelligent, a couple of proto-beatniks with beards and berets, and several with hobbies too fascinating to resist. My roommate was an expert on streetcars, and we spent Thanksgiving break riding every subway line in New York City and every trolley line in Newark and Hoboken. Ditto in Philadelphia. And the streetcar hobby was on top of the 23-plus hours a day I was spending as a volunteer at the college radio station, WRMC.

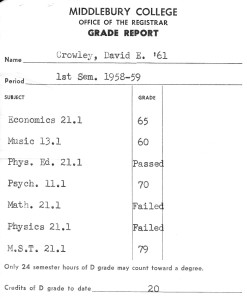

I had buried studies and class work somewhere in the deepest recesses of my mind and had passed from blind, unrealistic optimism into deep denial. Sure, I was afraid, but I believed that the grades would take care of themselves—somehow. The approach of first-semester finals in January 1959 unleashed the panic that I had long suppressed with extra-curricular pursuits. There was no way I could pass physics and calculus.No amount of cramming could save me, and I knew that Middlebury tossed you out when you failed two courses. We had joked about students flunking out and having to go to junior college, or worse, to inferior urban diploma mills like BU in Boston. Now the humor was gone.

Out of desperation, I sought refuge in a collection of science fiction paperbacks that had accumulated in the Atwater residence. Maybe my predecessors in academic crisis had used these books as the sand in which they buried their heads, just as I was doing.

The notice of failing grades appeared in my mailbox, followed a day or two later by a short letter from the dean. The college was dropping me. I had flunked both physics and math. When I called my mother to deliver the news, she took a deep breath and said, “Well, I guess Joe and I will have to come up and get you. We’ll call you back tonight after Joe gets home.” She didn’t react with the hysteria that I feared, but I felt terrible anyway. They put a huge effort into my education, and I had failed them.

The next day I went to see the dean who offered his sympathy, but said that it was unlikely that I would ever return to Middlebury. The more I thought about what he told me about never returning, the angrier I became.

When my father arrived a few days later to collect me and my things, he seemed panic stricken. I hadn’t seen him so upset before. “What’s going to happen now?” he demanded. I don’t know if anything I said reassured him during our five-hour ride, but when we got to Marblehead I learned that my mother had been on the phone researching alternatives for me. It felt good to be home, with the impossible situation at Middlebury behind me. What the dean had said stuck in my mind and I began, at last, to think.

The first step was to get a job, which was easy. My father’s brother Paul, a vice-president of Sylvania, had arranged summer jobs for me before at one of their factories in Salem, and was willing to do so again. With an income I felt independent enough to plan without worrying about burdening my parents. My anger at the Middlebury dean drove me forward.

With the failure in physics and calculus, I had no problem realizing that I wasn’t suited for engineering. Psychology seemed interesting, and I thought it would be nice to help people. I went into Boston University and signed up for two night school courses in psychology and one in public speaking. Now I had to suppress BU’s reputation as a haven for flunkouts from better schools, and forget the jokes about diploma mills.

A course in social psychology opened my eyes to the possibilities of research, and taught me an important lesson about the relative quality of students. Many of the men at Middlebury seemed to focus on fraternities, drinking, cars, sports and sex. For these guys, Middlebury was a convenient place to learn to ski, pick up girls, and to pursue some serious drinking. My BU classmates could not have been different; they were motivated to learn. All worked full time in the day and none had much use for nonsense like getting drunk.

The professor took us through his lab where he studied group communication and I was fascinated by his clever experimental designs. Another student on the tour invited me to a party in an apartment near the campus where we discussed psychology and other academic subjects. It’s possible that I had one beer. In class, a woman in her mid-thirties sat beside me, and we talked. She was a nurse earning her college degree at night and had served in World War II. I was twenty and said nothing to her about the warm surge of affection that I felt.

One night, a student asked a question about the previous week’s lecture. The professor paused to think, and another student whipped out her steno pad and read back the instructor’s exact words. Wow! I hadn’t seen anything like that at Middlebury.

Determined to succeed, I typed all of my class notes on my evenings off and kept them in binders. I wasn’t going to depend on the slovenly note-taking that had contributed to my failure at Middlebury. I know that my parents were relieved to see me taking charge of my education. My father helped by commuting to Boston by train, so that I could have the car to get to my job in Salem and to class in Boston at night. My mother did light shopping on foot in downtown Marblehead and waited for the weekends for bigger errands. Many years later, she said that the time in 1959, when I lived at home and went to school in Boston, was one of the happiest for her.

At the end of the spring semester at BU I had two A’s and one B. I knew then that I was on the right track with psychology and that I might exact my revenge on the dean at Middlebury by gaining readmission and proving him wrong. I knew the procedure: write a letter to the Administration Committee at the college demonstrating that you had mended your wayward habits, and that you could succeed now. I began to compose it in my mind.

My mother suggested that I really didn’t have to work, and could go to summer school at BU full time. I took additional psych courses and elementary German which I knew that I’d need for graduate school. One of the professors announced a term paper, sending me into a panic. I didn’t know where to start. When I told my mother, she offered to help me with the research and even to type the paper. I was embarrassed by her generosity. After all, she and my father had sacrificed so much for me, and as an adult, I should be proceeding on my own. I typed out eleven pages on the development of vision in infants and got a B.

By the middle of August 1959 I had my summer school grades: four B’s. With the letter to Middlebury College mostly written in my head, I headed upstairs to my attic room in our Marblehead house to type it out. I had a good supply of erasable bond paper and my favorite blue carbon sheets. I worked slowly, trying to avoid mistakes. I requesting readmission to Middlebury, chronicled my academic downfall, my change from physics to psychology and my redemption at BU. I dropped my transcript into the envelope with the letter, mailed it on August 21, 1959 and waited.

Less than two weeks later I had a response from the college re-admitting me. The following weekend my parents drove me back to Middlebury for the beginning of my junior year. I couldn’t wait to confront the dean.

He was all smiles this time, and I was polite as I expressed my gratitude for his good wishes. I said nothing about my anger at him which, for some reason didn’t subside with my readmission, but instead grew stronger, fueling revenge fantasies that lasted for seven years.

Still determined to show him how badly he had misjudged me, I looked for an opening. An opportunity came when I returned to Middlebury again in the spring of 1966 with a Princeton doctorate under my belt, this time to interview for a faculty post.

The dean and I found ourselves standing, side-by-side in the men’s room near the end of my interview. I savored the irony of our relative positions then and now. “We’re equal now,” I thought, and I realized with a smile to myself that I had forgiven him.

Nest week: Dave’s first car: the 4CV .