It hadn’t occurred to me to smoke when I was in high school; both parents smoked unfiltered cigarettes, but among kids my age, only the thugs, greasers and delinquents did. None of the college bound kids smoked.

It all changed when I got there myself. I was 18 and devoid of social skills when I arrived at Middlebury College in the fall of 1957. Unable to make friends, I sought refuge in the college radio station, WRMC, where I hoped to sharpen my electronics skills and gain some degree of social acceptance. Maybe, I thought, the shared activity might generate some companionship. Besides, there were a couple of girls who worked at the station and maybe I could gather the courage to ask one of them out.

Most people on the radio station smoked. In fact, the American Tobacco Company paid for our United Press teletype service; all we had to do was play their Lucky Strike® commercials on the air. And it gave out little sample packs of five cigarettes each on campuses nationwide, including Middlebury.

In the dorm and at the radio station, the people who smoked seemed relaxed and at ease with each other. They didn’t have problems making friends or asking girls out. I picked up a sample pack of Lucky Strikes and smoked one. Of course, it tasted terrible, but I knew I had to stick with it if I wanted the social benefit that I saw in smoking. After I few days I got used to the taste and told my mother on the phone that I had started. “I’m sorry to hear that,” she said, “but of course Joe and I have smoked for years. I guess everyone does.”

Later that fall Middlebury’s fraternities held their annual “rush,” in which they looked over the male members of the freshmen class for potential members. Each of the ten fraternities hosted events called smokers on Friday and Saturday evenings which we attended in groups over a period of several weeks. I felt no less awkward and embarrassed at these gatherings than I had before, even with a cigarette in my hand or sticking out of my mouth. And none of the fraternities selected me; instead I wound up in an independent mens club.

I kept smoking unfiltered Luckies throughout college and succeeded in making a few friends; some smoked and some didn’t. Two of them had pipes which required constant reaming and scraping with a special tool they carried. When I tried one it tasted terrible in spite of the pleasant aroma.

In my first year of graduate school at the University of Vermont in 1961, I met a young woman, a non-smoker, who became my fiancé. Her name was Helene and after our engagement two years later she produced a very funny hand-drawn cartoon showing what I looked like as a smoker. There were spikes of fur coming out of my eyeballs and mouth, ugly spots on my face and hair sticking out in all directions. The inspiration for her sketch had come from the Surgeon General’s first report on the health hazards of smoking issued in January, 1964.

By that time, I had transferred to Princeton to complete my doctorate and very few of the people in the lab where I worked smoked. After six years of what I called real cigarettes—those without filters, I quit cold turkey. I had no trouble, but I joked that if I ever had another cigarette, I would inhale so deeply and with such satisfaction that the smoke would pour out the eyelets where I laced up my shoes.

Helene and I married in 1965 and moved back to Middlebury where I had a teaching job. Our daughter Hanna was born three years later. A year after that, in 1969, we moved to St. Louis, where I took a research appointment, but Helene was not happy. We separated in August 1970 and divorced in May 1971.

The stress was too much; I powered myself through the initial months with Librium and attempted to cover my anxiety and grief with a return to cigarettes. This time I chose filters as less risky than what I had consumed before. I smoked Kent Golden Lights® for 16 years.

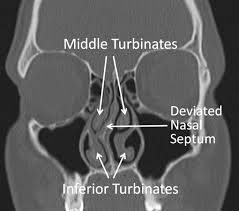

In 1985 I took two smoking cessation classes, and in the second one acquired some samples of Nicorette®, the nicotine chewing gum. I worked then for McDonnell Douglas and carried the Nicorette in my brief case every day until February 28, 1986 when the boss decreed that smokers would have to move to a separate part of the office. I dropped my cigarettes into the wastebasket and took out the nicotine gum. I haven’t smoked since. It wasn’t until 1996, 38 years after I started smoking and 10 years after I quit, that second hand smoke began to irritate my eyes.