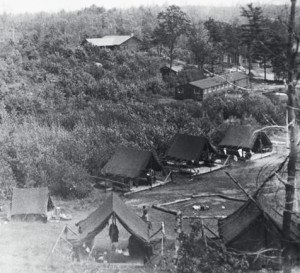

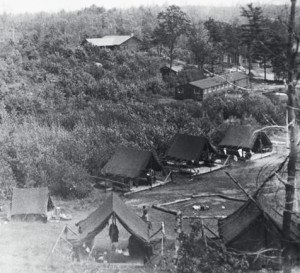

Skunk Hollow at Camp Norshoco with platform tents and the old dining hall and post-office ( barely visible at the right..) The new dining hall is near the top. Photo by Dave Crowley, age 14

I might have been 16 when one of the leaders at Camp Norshoco in Alfred, Maine, showed me a small album of color photos depicting log cabins situated at the edge of a dense pine forest. When I saw the pictures, in 1954, the camp was mostly open fields with a couple of low hills and patches of new growth hardwoods, grasses, shrubs, and a swampy creek. “How I missed the old cabins in the pines,” I thought to myself, adding, “They must have been wonderful” In fact, I had never seen them, because in the fall of 1947, a series of fires had destroyed over 300 square miles of Maine forest, including Camp Norshoco, three years before my first two-week visit to the camp in 1950.

We campers, from various Boy Scout troops in Marblehead, Salem and other North Shore towns slept in tents on wooden platforms in three encampments: Skunk Hollow, where I stayed two or three summers, a second site whose name I’ve forgotten, and Little Egypt, named for its Army-surplus square pyramid tents. There were three buildings: a long prefabricated dining hall with a corrugated steel roof and a kitchen at one end, a small infirmary and a modest administrative structure that doubled as a post office. There was a lake, in which we swam and canoed, called, as far as I knew, Lake Norshoco. In reality its name was Bunganut Pond – as I discovered from a recent Facebook posting. The name Norshoco, I believed then, referred to the Indian tribe that had once lived on its shores.

Little Egypt was reserved for Scout troops that attended Norshoco together, with their own leadership rather than as individuals mixed in with kids, as I was, from other troops. The most cohesive unit to attend Norshoco while I was there was Troop 83 from Ste. Anne’s parish on Jefferson Avenue in Salem, Mass. Its scoutmaster was an energetic priest named Father Bourgault. I had never seen a priest out of uniform before Fr. Bourgault, yet there he was, walking across the parade ground, pot bellied, and wearing an undershirt, shorts and sneakers. I didn’t believe that he was really a priest until he celebrated Mass for us the next Sunday, in full vestments.

Marblehead Boys in Skunk Hollow 1951: Rear – Joe Homan, Middle – John (Jack) Collins, Freddy Petersen, & Ross Goodwinn, Front – Paul Meo & Warner Hazel (?). Photo from Chris Brown

Troop 3 in Marblehead, where I was a member, didn’t seem cohesive at all. It wasn’t the fault of our leaders; it was, instead, the large number of misfits among us, or so I believed. I envied the other troops like Father Bourgault’s in Salem, and Troop 11 from St. Andrew’s Methodist in Marblehead. They each had at least a dozen Eagle Scouts; we had one.

In 1953 a group of us from Troop 3 spent a week in Little Egypt at Camp Norshoco, along with one of our Assistant Scoutmasters. The first two days were fun, but the rest of the week was absorbed in drama generated by the destructive antics of two of our misfits,

During my second stay in Skunk Hollow in 1952, I developed painful headaches, and lay on my bunk during a hot summer afternoon. My three tent mates and some others were not sympathetic, taunting and throwing shoes at me while I tried to rest. By the end of the day, I had enough of this mistreatment and headed to the infirmary; I was feeling feverish and sick all over by then.

The infirmary nurse was the only female in camp and seemed to be in her thirties. She had medium length dark curly hair and was very attractive in her white uniform. She took my temperature, fed me some fluids and aspirin and put me in a cot. I went to sleep and woke up feeling better. She appeared with food on a tray from the dining hall and asked if she and her son could eat with me. I had noticed the young boy, maybe about eight. He wasn’t an official camper and he stayed mostly in the infirmary with his mother. He had some ugly scars on one leg, centered around the back of his knee, and walked with a pronounced limp. I sat on the edge of my cot to eat my supper, while the nurse and her son sat on another cot. I was the only infirmary patient. Afterwards she and her boy retreated into the dispensary beyond the small patient ward; their bedroom was in the back, out of my view. I went back to bed and turned over, and as I looked up, I saw her walking past the open dispensary door in just a white slip.

“Oh, I’m sorry,” she said, “I forgot you were here. I hope you don’t mind me in my slip. I don’t get many overnight patients. My son is sleeping in the bedroom, so I change in here to avoid disturbing him.” She disappeared and came back in a bathrobe. “ I need to tell you about Paul,” she said, and in that instant, by addressing me as another human being who might be curious about the scars on the boy’s leg, she granted me a degree of adult respect that no one had shown me before. To her I wasn’t a patient requiring professional distance or a child needing supervision or discipline; I was another person, just as worthy as she was. Her appearance in the slip hadn’t seemed at all immodest to me, no more so than seeing my own mother in one.

She continued, “Paul was a baby when he pulled over a pot of boiling water on the stove scalding his leg. It was just an accident, but in healing, the burn left these very tight contractures that I have to work and massage every day to keep his leg and as flexible and mobile as possible. When he’s a little older, he’ll need an operation on his tendons.”

Camp Norshoco Patch

I awoke the next morning feeling fine and went back to my tent mates who didn’t bother me again. The nurse had given me refuge and the gift of respect. So empowered, I thought again about the name of our camp − there never were any Norshoco Indians, it was simply a contraction of our Boy Scout district: The North Shore Council.

Next week: Troop 3

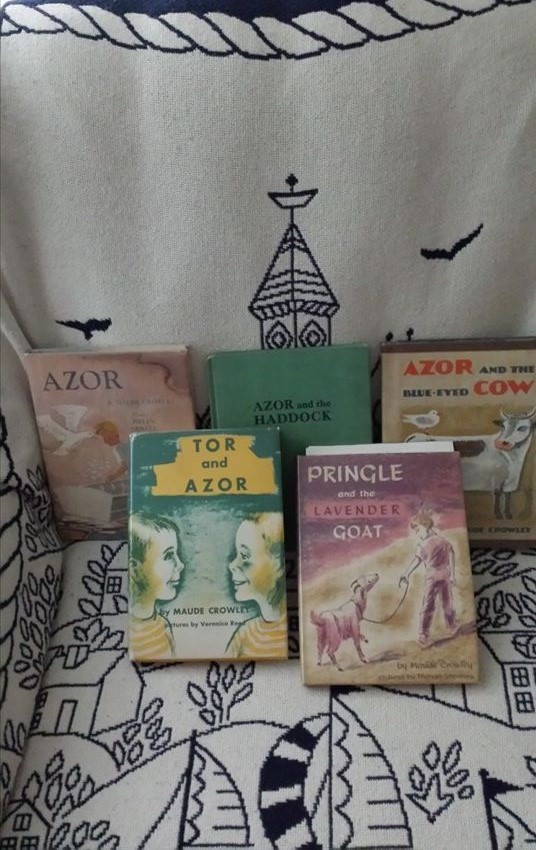

How the Town of Marblehead and its people inspired my mother, Maude Crowley, to produce this treasured series that illuminates a child’s life in a time long past. I have the inside story and would be willing to produce a small book that reveals the author’s background and what it took to have the five books published by Oxford University Press. Plus, I have loads of press and radio interviews, high-quality photos, and the original watercolor illustrations by Marblehead artist Ingrid Selmer-Larsen that were intended to go in the series.

How the Town of Marblehead and its people inspired my mother, Maude Crowley, to produce this treasured series that illuminates a child’s life in a time long past. I have the inside story and would be willing to produce a small book that reveals the author’s background and what it took to have the five books published by Oxford University Press. Plus, I have loads of press and radio interviews, high-quality photos, and the original watercolor illustrations by Marblehead artist Ingrid Selmer-Larsen that were intended to go in the series.