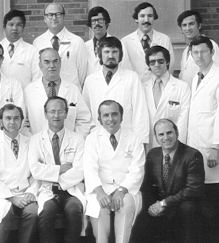

When I began my job in the Department of Otolaryngology at Washington University Medical School in St. Louis, in 1969, I kept my ears open and picked up all sorts of medical information. Sometimes it came from the grand rounds I attended every week, where cases and scientific papers were discussed or simply from chatting with the residents that I taught in class or who worked in my lab. After I had been there a few years, I had a question for one these physicians, a guy who had some expertise in respiratory dynamics.

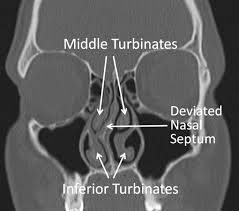

“Irv,” I began, “I think I have a deviated septum and I have trouble breathing though my right nostril. Should I do anything about it?” “Well, you might think about it,” he said. “It can lead to trouble later in sleeping or even in your bronchial tubes, sinuses or lungs.” We both knew that surgery was the only option – something called a “submucosal resection” done under local anesthesia. What Irv didn’t have to say was that smoking cigarettes, which I did at two packs a day, was a far greater risk to my respiration than any deviation of my septum could be. But Irv wasn’t my physician, and the residents knew not to give unsolicited medical advice to their colleagues and friends.

It took another year of stuffiness and obstruction to convince me to get it done. I wasn’t getting any air at all on the right side when I asked Irv to suggest a surgeon. “Don Sessions is pretty good with noses,” he replied. “You’ll be in and out in less than a half hour.” A couple of days later in his office, Don took a look and said, “Yup. It sure is. Let’s get you scheduled.”

I checked into Barnes about a week later in the early fall of 1977, a couple of months short of my fortieth birthday. My girlfriend Nancy had driven me and stayed with me in the room for an hour or so. When I said that I was frightened she reminded me how minor the surgery really was. I calmed down, and after she left, a resident came in to give me a pre-op physical. “Hey, chief, aren’t you the guy who taught us about cochlear microphonics and all that auditory stuff? “Yeah, that was me,” I replied as he checked me over. When I woke up the next morning I wanted to reassure myself with my usual morning routine of shaving and showering—and smoking a couple of cigarettes which was allowed then in hospital rooms.

After I rode a gurney to the OR, a nurse pinned me to the table with a sheet and started an IV. I was still scared, and it must have shown. “Would you like a little Valium to settle you down?” she asked. I nodded. “Yeah,” she said, “here it comes.”

Then Don Sessions came in along with a couple of residents whose voices I recognized from behind their surgical masks. The nurse scrubbed my face with Betadyne and placed a drape over my eyes and a second one over my lower jaw.

“OK, here goes,” Don said as he jabbed me with a long needle, right above my upper lip, directing it from left to right. It hurt like hell. “Scream, curse, do whatever you need to,” he said as he emptied half the syringe into me. Then another shot in the same place, this time from right to left, followed by two more directed upward along the outside of my nose. My face was starting to feel numb. After two more shots inside my nose, Don said, “Here’s a little nose candy,” and placed some powdered cocaine up inside each nostril.

After that there was a lot of scraping, crunching and chiseling. Maybe it was the Valium and cocaine but I didn’t mind. I’d had a lot of dental work done under local anesthesia, and this didn’t seem much worse. But then from under the drape I saw a long chisel headed toward me. “Now just give it a hard tap,” Don told the resident who was holding small mallet. My head shook with the impact. “No, you’ve got to belt it lot harder,” Don said. Now I was scared. Was this the resident’s first try? Would the chisel go too far this time and plunge into my eye or my brain?” There was another sharp jolt and my head shook again. “OK, there it is.” And he held up a triangular piece of bone for me to see.

“We’ll stitch you up now. We’re due at Stan Musial and Biggie’s for lunch, and we have to get moving.” I felt a twinge of disappointment; had I not been pinned down to the operating table, I could have been joining them at the restaurant. He installed a plastic splint inside my nose on both sides and pinned it in place with a heavy suture that he drove through from one side to another with a straight needle. Then he stuffed what seemed like several yards of gauze packing into my nose. Of course I will still very numb.

Back in my room, the nurse put an oxygen mask on my face since now I could breathe only through my mouth. I reached for the phone to call my parents in Marblehead and spoke with my father assuring him that I come through the operation OK. Then I dozed off until the resident came in to check up on me. After he left, I wondered if I could smoke with only my mouth to breathe through. I went in to the little bathroom and lit a cigarette. I took a puff inhaling the smoke. Then I blew it out—no problem.

I went home the next morning and stayed there for a week. I was sore and there was a little bruising around the bridge of my nose, but I could sleep OK. I got used to breathing though my mouth. Of course the packing was uncomfortable; it looked terrible and it dripped. At the end of the week I went back for my check up. Don was out of town, so another staff physician took out the splint and all packing and cleaned me up. I could breathe again.

Back at work I joined my usual lunch companion in the cafeteria: Roy Peterson, a professor of anatomy who supervised the laboratory where the medical students dissected their cadavers. I told him about the little piece of bone they had taken out. “Yeah, that’s the vomer,” Roy said. “If you like we can go upstairs and I show you on one of our cadaver skulls.” I was curious and wanted to see what the bone looked like in its normal position.

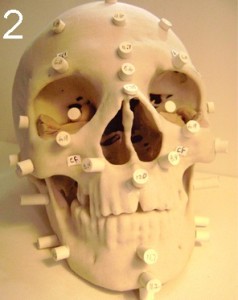

A cast from an Egyptian mummy showing a right-deviated nasal septum. The numbered pegs aid in reconstruction of the face.

We had to go through the dissection lab to get to the display cases with the skulls, and I was relieved that all the bodies were covered with sheets. I may not seem squeamish, but partially dissected people are too much. At the display case, he pointed out the bony parts of the nasal septum that remained in the skull. “There’s the vomer right at the base of the nasal opening—see, that little triangular piece. You know that septal deviations are very common; you can even see it this skull. It’s usually not bad enough to obstruct breathing, though. They even found deviations in Egyptian mummies.”

I wondered if the ancient Egyptians had the same trouble breathing that I had before the surgery. Probably not I had to admit. They didn’t smoke.