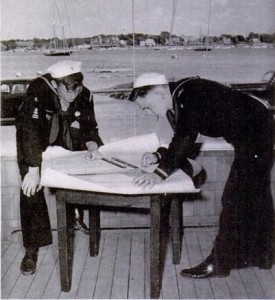

Marblehead Sea Scouts in their whaleboat off Fort Sewell. From Hartley Alley’s “A Gentleman from Indiana Looks at Marblehead” Bond Wheelwright Company, Freeport, Maine1963

I remained with Boy Scout Troop 3 in Marblehead until 1954 when I was 15, around the time that our scoutmaster, Dave Eckhardt, was drafted into the Army. Many of us knew of the illustrious Sea Scout Ship Marblehead, which had prospered in the 1930s, winning the National Flagship Award and appearing in a Life Magazine feature in 1940. All of those boys and their leaders went into the military in World War II and after the war the Ship was revived but dissolved a few years before I became eligible to join.

A number of us in Troop 3 lobbied our parents and sponsors at the American Legion to revive the Sea Scout Ship again. An adult committee, which included my father, met with Legion and Scout officials who agreed to re-charter the Ship to begin meeting in the fall of 1954. Our new Skipper was to be Don Sweet, who had been a member of the 1930s group and who had served in the Merchant Marine during World War II.

When we met, Don told us to scrounge surplus navy uniforms, both wool winter blues and cotton summer whites. My mother knew a man about my size who had served in the Navy. She drove me over to his house in Beverly where he handed over his old uniforms with the sailors’ bell-bottomed pants. We stopped at Almy’s in Salem for the Sea Scout patches which she sewed on the next day.

Each week we gathered in uniform at the American Legion Hall. Our skipper directed us to lay out the room like the deck of a ship with wooden stanchions connected by ropes representing the rail. He taught us the proper naval protocol for boarding a ship, including proper salutes and piping officers aboard with a Bosun’s pipe.

We needed a whaleboat which one of our leaders located in Georgetown. We drove about twenty miles one evening in his pickup truck with a trailer hitch to bring it back to Marblehead. The boat was a little over twenty-six feet in length with four benches, or thwarts, accommodating eight oarsmen. A coxswain at the stern used a steering oar to direct the boat while an officer sat at the bow.

The American Legion did not allow us to use the “Beachcomber” cottage across from Fort Sewell Beach that the earlier groups has used as headquarters. But they did let us store and maintain our whaleboat right behind the cottage where we could launch it easily at high tide into Little Harbor. We fixed it up, launched it and set out to practice our rowing skills with our skipper’s son Don Sweet, Jr. serving as coxswain. After several weekend trips around Marblehead Harbor we learned to handle the boat well and were prepared for a big event coming up in June.

Sea Scouts Dick Bridgeo and Walter Bartlett on the porch of the Beachcomber Cottage. from Life Magazine, August 5, 1940

Several Sea Scout Ships from the North Shore of Boston held an annual regatta at Stage Fort Park in Gloucester timed to coincide with the festival of St. Peter, the patron saint of fishermen. A naval vessel, a cruiser, made a courtesy visit for the festival and some of the Scouts rowed out in their whaleboats for a tour of the ship.

To reach Gloucester from Marblehead we rowed about fifteen miles across Massachusetts Bay taking maybe two hours with a light wind and favorable currents. Don Sweet, Jr. steered from his coxswain’s perch at the stern while Don, Sr., our skipper, directed from the bow. We wore casual clothes, saving our summer whites for formations and for a night on the town in Gloucester. We carried our clothes in sea bags in the whaleboat with us while my father and some others brought the rest of our gear to Gloucester by car.

We were pitching our tents in the park when I heard a scream behind me. I turned to see Don Sweet, Jr. running in circles having hit his hand with the back of an axe while pounding in a tent peg. My father tackled him, bringing him to the ground and held his bleeding hand steady. Don Sr. arrived on the run and bundled his hysterical son into a car for the short drive to Cape Ann hospital. They returned to the campsite a couple of hours later with the younger Don sporting a fat bandage on his left hand. I hadn’t expected my father to act so quickly. I was proud of him for his decisive action in an emergency.

That evening we donned our whites and walked towards the Gloucester fish piers to enjoy the carnival set up to celebrate the Feast of St. Peter. The crew of the naval vessel visiting Gloucester had shore liberty and wore summer whites just like ours, except for the Sea Scout patches. A small group of us, Dave Fleming, Paul Meo, Charlie Pike, “Pic” Harrison and I, stopped at a booth selling ridiculous joke hats. Paul Meo and others dared me to buy a very wide, floppy beret: yellow with blue and pink polka-dots. I bought it stowing my white sailor’s cap into a pocket and putting the silly hat on my head. We stuffed ourselves with hot dogs and other snacks and decided after a while to walk back to our camp site in the park.

We had almost reached the Gloucester Fishermen’s Monument on Western Avenue when a jeep manned by sailors with Shore Patrol arm bands stopped beside us. “Come over here!” the driver barked at me. “You’re out of uniform!” I realized right away that the Shore Patrolmen had mistaken us for sailors from the cruiser, and that if I didn’t produce my Sea Scout card quickly I’d be on my way to the brig. I snatched the polka-dotted beret off my head and fumbled for my wallet. The man looked at my card and said OK before driving off.

The next morning, a Sunday, we Catholics attended Mass, celebrated by a priest in full vestments in front of a tent in the park. Two Gloucester Sea Scouts served as altar boys. Afterwards we competed in a whaleboat race, coming in second despite an exhausting effort at the oars.

Our fathers returned with their cars to pick up our gear. We broke camp, and started the long row back to Marblehead Harbor. The current which had favored us on the trip to Gloucester now opposed us and the rowing got very hard. We put our backs into it but the water towers and other landmarks on shore barely moved in relation to us. After an hour and half we hadn’t yet completed a third of our journey. A friendly man in a powerboat pulled alongside. “Want a tow?” he asked. We tossed him a line and relaxed all the way back to the dock in Marblehead.

The Beachcomber Dory Club, occupants of the building before the Sea Scout took over. From the Peach Collection

Beyond the camping expedition, our skipper and his associates taught us numerous nautical skills and took us on expeditions which included a visit to an aircraft carrier, a weekend at Pease Air Force Base in New Hampshire, and a short cruise on a destroyer. These Sea Scout adventures were the high points of my late adolescence, but I gave little credit to our leaders for arranging them. As kids we had no idea what it took to set these plans into motion.

Years later I read that Don Sweet Jr., had died in Florida in 1995 at age 55 and that Don, Sr. died in August 2001 at 85. My mother kept the polka-dotted beret from the St. Peter’s festival in Gloucester at our home in Marblehead until it disintegrated.

Next week: Crawford’s Notch

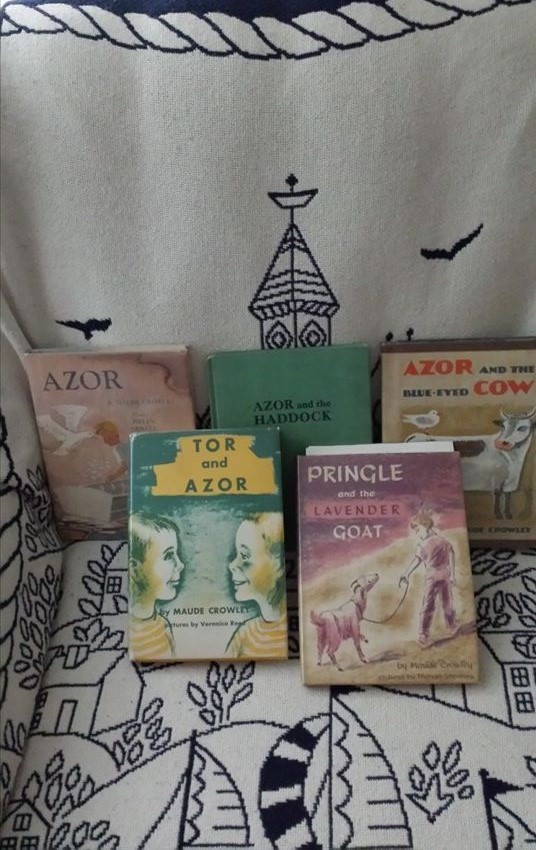

How the Town of Marblehead and its people inspired my mother, Maude Crowley, to produce this treasured series that illuminates a child’s life in a time long past. I have the inside story and would be willing to produce a small book that reveals the author’s background and what it took to have the five books published by Oxford University Press. Plus, I have loads of press and radio interviews, high-quality photos, and the original watercolor illustrations by Marblehead artist Ingrid Selmer-Larsen that were intended to go in the series.

How the Town of Marblehead and its people inspired my mother, Maude Crowley, to produce this treasured series that illuminates a child’s life in a time long past. I have the inside story and would be willing to produce a small book that reveals the author’s background and what it took to have the five books published by Oxford University Press. Plus, I have loads of press and radio interviews, high-quality photos, and the original watercolor illustrations by Marblehead artist Ingrid Selmer-Larsen that were intended to go in the series.