When I arrived at Middlebury College in Vermont in the fall of 1957 at age 18, I was planning to become an engineer, transferring — with good physics, chemistry and math grades — to MIT after my junior year. I had done well in these topics in high school, and I had always enjoyed fiddling with radios and simple electronics. After a few weeks at Middlebury I went into the basement of the Student Union building to check out the college radio station, WRMC. I could learn more about electronics, I thought, if they would take me on as a volunteer to do technical work. An upperclassman showed me around. In the control room were two large turntables built into a bench on either side of a sloping panel with a lighted meter and six black knobs with a bunch of lever switches. Large windows on either side of the control room allowed the engineer to see into the studios on the left and right. “Marty” (a pseudonym) is our chief engineer,” the upperclassman said, “He’ll be back later this afternoon and can answer your questions about the electronics.”

Marty was from Maine and worked with large mainframe computers for the local gas company during the summer, he told me when we met. He led me out of the studio, past storage cages with provisions for the Student Union coffee shop upstairs to a small back room which contained a teletype machine fed by United Press International. “American Tobacco pays for the UP teletype at many college stations like WRMC” he said. “All we have to do is air so many Lucky Strike commercials a day. They’re on those transcription disks.” He pointed to a stack of sixteen-inch records in sturdy manila sleeves leaning against the wall near the teletype. These records, I could see, would fit on the Gates turntables I had seen in the control room, but were too big for home phonographs.

In an alcove behind the teletype was a large home-built electronic chassis with glowing tubes and wires sitting on a shelf. It hadn’t been dusted in a long time. “That’s the transmitter,” Marty said. “It feeds into the old class-bell wiring underground that goes to all the buildings and dorms. They don’t use the bells anymore so we use the wires as an antenna.”

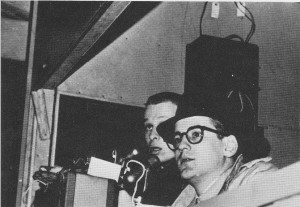

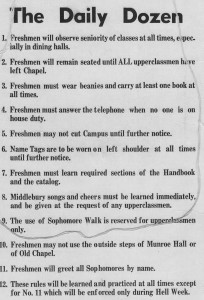

The next day I came back to learn how use the equipment in the control room. Jim Tracy, a sophomore, showed me how to cue records and operate the switches and knobs while always watching the VU meter to keep the needle out of the red “distortion” zone. Later that day I met another sophomore who had a country and western show and who was willing to let me do the engineering for him. After a few weeks I was comfortable in the control room and asked if I might do some announcing too; I thought that it might help with my stuttering.

They let me start with the news, reading selected items from the UP wire. I did fine without stammering. You had to edit your copy beforehand, they said, because sometimes there were typos and other errors in the teletype feed. When Pope Pius XII died on October 9, 1958, the first UP bulletin read “POOP DEAD.” I went on to read other material and served as News Director for awhile. My main responsibility was to keep the teletype supplied with fresh ribbons and a full paper roll. God forbid the paper should run out in the middle of an important story overnight. It happened once and I got into big trouble.

Eventually I hosted my own classical music show. It was very easy to run the entire station from the control room, announcing, cueing up records and manipulating the knobs and switches on the control board. You didn’t need a separate engineer and announcer if the show wasn’t too complicated to produce.

WRMC covered Middlebury College sports by sending one or two reporters to the home and away games. We leased a special line from the telephone company for each game we covered, and carried a homemade portable console to connect the microphone to the phone line in the press box. This black box was called “Baker’s Battery Bastard,” or the BBB after the former student who constructed it.

Peter Talbot was one of the juniors who were most active at the station when I was a freshmen. We envied him, because he had a summer job working on a real radio station in Connecticut. He also had a great bass voice that projected well on the air. One day he showed us a trick with which an announcer could recreate the play-by-play for a baseball game from a properly kept score card and a recording of crowd noises. One person could create the illusion alone in the studio and the listener would believe that the man on the radio was actually at the ball game:

It’s a bouncing grounder. And, OOOOOh, it’s by the shortstop on one hop. Johnson charges for third…[crowd noise up]… The throw from center. Not in time! Heeee’s safe!!!…[more crowd noise]…

The deception depended on the listeners not knowing exactly when the game was played, and, of course, on a ready willingness to suspend skepticism every time they turned the radio on.

Next week: The transmitter